I’m writing this piece, about the film ‘The Zone of Interest’, on the evening of Monday 11 March, 2024. I sketched a few rough notes out last night, then went to bed – waking this morning, of course, to news of the Oscar winners. I like to think this movie received the two awards that become it the most: Best International Feature, and in particular, Best Sound.

The sound design (by Tarn Willers and Johnnie Burn) is already one of the most noted aspects of the film – even if you’ve only read a review or two, you will be aware of the tension between what you see and what you hear. I also want to praise the film’s immaculate visual storytelling, and its extraordinary power to turn our gaze back on ourselves.

So, I was interested to read about director Jonathan Glazer’s acceptance speech, where he spoke about the film addressing dehumanisation in the present, as well as the past. Whatever your views on the nominees and eventual winners across the board, it speaks to our times that three of the films in contention – ‘The Zone of Interest’ alongside ‘Oppenheimer’ and ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’ – were the work of male directors who have made past study of damaged, violent men, now turning their attention to historical figures who, in different ways but arguably from the shadows, became architects of mass slaughter. To paraphrase Marlowe’s Mephistopheles: this is hell, nor are we out of it.

A short warning note. While it seems facile to talk of ‘spoilers’ in a film with this subject matter, it is still a deliberately-paced work with key narrative developments and fully-earned moments of power. Knowing about some of these in advance could certainly lessen their impact. I discuss the film freely below. With that in mind – please see it first, if you plan to, then return to this post.

*

The ‘zone of interest’ is a Nazi euphemism for the area of land containing the Auschwitz complex. We follow, at first, daily life inside the handsome residence of camp commandant Rudolf Höss (played by Christian Friedel) and his family. Höss goes off to work in the morning, returns at night: his wife Hedwig (an astonishing performance from Sandra Hüller) – proud of her husband’s achievements and their resulting status – manages the house, children and servants with brisk efficiency, commandant of her own domain.

However, the property is literally next door to the camp: in fact, they share a long stretch of the perimeter wall. We stay with the household: the camera never shows us the atrocities being executed just over the garden fence. But we can hear them. The constant thrum of mechanised murder is audible beneath every conversation. At any given time, you could be hearing grinding machinery, transportation, slamming doors, burning furnaces. Gunshots and screams provide more identifiable punctuation.

The Höss family are apparently immune to the noise, never once acknowledging its invasiveness. Against this queasy, unrelenting soundscape, the cumulative effect of each casual, callous act they commit bewilders and sickens us. Every human moment has an inhuman underlay: from gifting the staff clothes and accessories stolen from the murdered prisoners, to fertilising the garden beds with their ashes.

But the film refuses any easy answers. We see Rudolf as a caring parent (one child sleepwalks, possibly a sign that vulnerability has taken fragile root in the household) and animal lover – who has clandestine sex with a prisoner. We see Hedwig as a doting mother (she has a slightly stiff, awkward walk – perhaps the lasting impact of giving birth five times, or who knows what else?) and aspirational garden designer – who turns on her servants at a whim.

It presents the couple with all-too-familiar domestic setbacks – chiefly his promotion and transfer away from Auschwitz causing a temporary fracture in their idyll. It tests for chinks in their mental armour and forces us to confront their selective psychosis.

*

Given the attention justly paid to the sound design, I think it’s illuminating to focus for a while on what Glazer does choose to show. Any director who chooses to represent the Holocaust must surely make an individual decision on how best to respect the subject matter. Famously, Claude Lanzmann’s ‘Shoah’ – as much document as documentary – is assembled entirely from personal testimonies, with no footage or dramatised content, as if attempting to depict such events would somehow dilute or sanitise them. It seems to me that in dramatic cinema, some kind of shield, some distancing element, is often used to make the viewing experience tolerable: two examples that come to mind are László Nemes’s ‘Son of Saul’, where the inmate protagonist is mostly in sharp focus, centre-screen, while camp activity surrounding him is more indistinct, implied; and Steven Spielberg’s ‘Schindler’s List’ with its almost merciful layer of black and white.

Glazer’s approach seems austere in comparison. Our exposure to this group of Nazis – the central family and visiting relatives, colleagues and associates – is frank and untempered. The Jewish ‘absence’ in the film (almost, if not quite total) is a symbolic masterstroke, denying us any concrete sympathetic presence and, worse, creating a microcosm of the world the Nazis envisaged. Even in a later scene where Höss is present at a work event and all he can think of is how he might gas everyone in the room efficiently, we only see him survey the scene: at that point, there is no view of the guests – no ‘substitute’ Jews – to draw focus from Höss’s placid evil.

The brief but telling character arc of Hedwig’s mother, visiting her daughter in her lovely new home, throws the utter degradation of Rudolf’s and Hedwig’s humanity into sharp relief. Glazer rightly resists any urge to make her a ‘warmer’ presence – she is thrilled with the family’s new situation, and as happy for the Jews to disappear as the next generation. But she cannot tolerate it on the doorstep. Everyone else in the house has been able to practise this detachment. But she awakes from a poolside doze to clouds of thick smoke rising into the sky. The glow of the furnaces takes away her night-time slumber, so she leaves without alerting the house. Hedwig reads her note and, ironically, consigns it to the fire.

*

For a film which can at first glance appear to use a verité, fuss-free approach, ‘The Zone of Interest’ is filled with visual flair and technique. Many of the shots are intricately composed to increase claustrophobia and discomfort. With sequences of Höss marching through various rooms and passageways, turning lights on or off, the house takes on a labyrinthine quality that – if the family are to shut out the terrors over the wall – turns it into its own kind of prison, from the film’s perspective, the actual ‘zone of interest’. Inevitably, perhaps – when one has favourite film-makers, it’s so tempting to see their influence everywhere – this combination of a detached, observational feel with deliberately formal composition made me think of Kubrick, another director interested in damaged, compromised male protagonists.

There is one shot that will stay with me for as long as I think about this film, not because it conveyed a particular horror, but for its overwhelming clarity. It’s important to note that while we don’t see the slaughter, we are visually aware of Auschwitz throughout, its barbed wire and towers looming over the Höss’s garden. There is a single scene where we see the characters at a table, but we are looking at them through a doorway, so they are compressed into an artificially small frame, trapped: while perfectly lined-up in the window behind them, we see a camp tower, bringing the suffocating presence of the camp to bear even in the Höss’s most interior spaces.

One of the film’s greatest achievements, in my view, is its willingness to walk the thinnest of tightropes: as the onlookers, we cannot identify directly with people capable of such vile acts, but we identify with certain other aspects of their lives. To be confronted with that truth is stifling: what would need to happen for us to become more like them? If they could succumb to such moral decay, why couldn’t anyone? Could we reach a point where we can block out the unthinkable like switching off a light in the passage?

The ‘normalisation’ of the Höss family is offset by the film’s occasional departures into non-realistic sequences that disrupt their narrative and allow a ‘voice’ on the victims’ behalf. A girl sneaks up to the borders of the camp when its dark to leave apples for the prisoners. These scenes are in a stylised monochrome dream-world: not the bravura black and white of a ‘Schindler’s List’, but rather a heightened negative effect. It inverts the moral vacuum of the Höss’s ordinariness into an artful personification of hope.

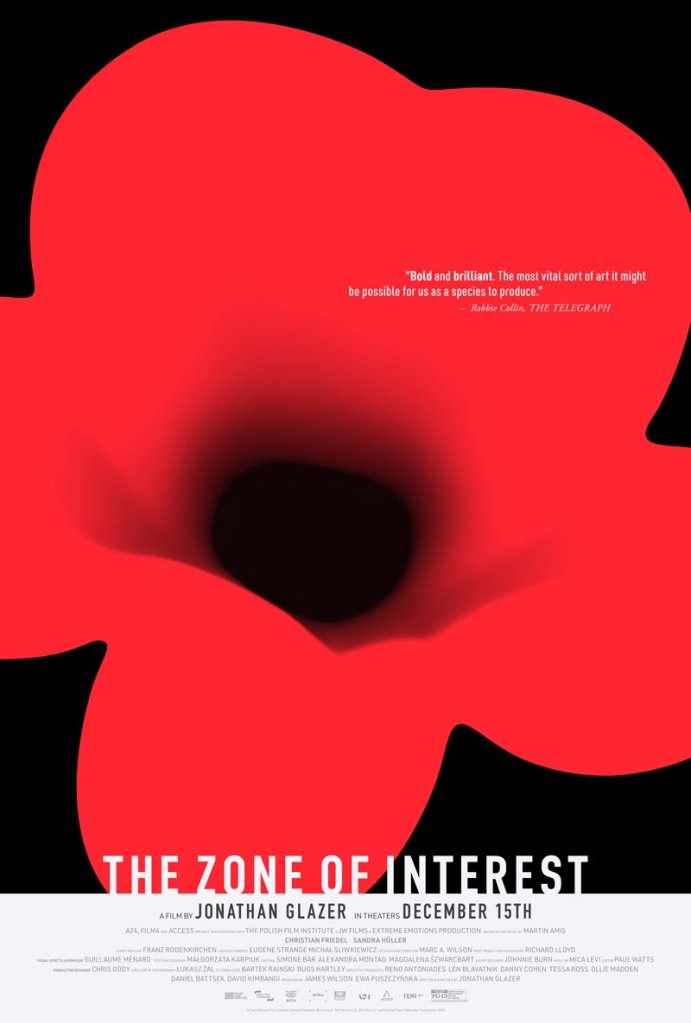

Later in the movie, a sequence showing the flowers in the garden settles on red petals, then zooms in to cover the screen in bright, even scarlet. The blood imagery is inescapable, like a visual scream of the lost. Powell-and-Pressburger vivid, it echoes earlier uses of red where their crimes stain their false notion of purity: Hedwig trying the lipstick of one of the camp’s detainees, and the horrific site of blood pouring off a pair of boots as they’re being washed.

The closing minutes of the film include the most audacious disruption. His return to Auschwitz approved to supervise the next phase of exterminations, Höss pauses on the way out of his Berlin office building. He dry-retches several times, but does not vomit. He is surrounded by darkness, above and below him in the stairwell, and at each end of the corridor where he stands, momentarily paralysed. We see a beam of light, then a door open at the end of the corridor, into the Auschwitz of the present day. Staff clean and prepare the museum. In a moment of heartbreaking irony, one starts up a vacuum cleaner just before coming into shot; the sudden intrusive hum instantly echoes the off-screen sounds from before. However, this calm, respectful efficiency now serves to expose the Nazis’ war crimes, not conceal them.

It is left to us to decide whether Höss shares this vision with us or not. If his sudden seizure was a point of no return, a moment where he could have emptied himself of the poison, he rejects it. We see him collect himself, and continue down the stairwell, into darkness. We are left staring into the abyss. Normal service has been resumed.

AA

(All images and stills from A24 publicity.)

Discover more from ARTMUSELONDON

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

brilliant! I had to watch it more than once to pick up all the nuisances.

LikeLike