This stunning exhibition educates as it enthrals. Strachan’s themes are serious and consistent: he focuses our attention on black people and their achievements that have been sidelined or obscured by our overwhelmingly white understanding – and re-telling – of history.

He navigates this over-arching topic through a wide range of disciplines and media: sculpture, paint, typographical art and graphic design, tapestry, audio and more. So, while the ideas feel fully unified – you are clearly in the company of one artistic mind and voice – you’re never sure exactly what you’ll see next as you move through the gallery.

Accordingly, I should warn of ‘spoilers’ – if you are able to go io the exhibition and want to preserve the element of surprise, please stop reading here and come back after your visit. Otherwise, I hope my descriptions and photos below partly convey the style and content of the show, especially for those who can’t get there in person.

*

One of the most stimulating aspects of Strachan’s work is its bravura, larger-than-life execution. For example, the ‘Ruin of a Giant’ sculptures present the heads of key black figures, such as Marcus Garvey, Harriet Tubman, and King Tubby, on a vast scale. The information panel tells us they are designed to look as if they might have been created and venerated by an ancient civilisation, and Strachan gives them appropriate signs of age and decay. I loved the anachronism of this, the stretching of the notional timeline back way beyond these figures existed, as though history itself was presaging their arrival, waiting for them to appear.

Timelines also blur and clash in the ‘Distant Relatives’ series, where Strachan juxtaposes traditional African/Indonesian masks with realistic, though unpainted, busts of more recent icons such as James Baldwin and Mary Seacole. Crucially, the framework displays each mask directly in front of the corresponding bust, so that if you stand directly in front of the exhibit, you can’t see the bust at all.

This felt to me like an elegant shorthand for showing how our (white, British, privileged) stereotyped cultural perceptions can still override the facts. Our fascination with the ‘other’ – attraction, fear and curiosity in a kind of shifting balance – means we are more comfortable keeping African heritage in the developing, ‘exotica’ box. It’s surely no accident that the busts remain plain, capturing the white overlay on history, and literally draining these luminaries of their colour.

Strachan is also unafraid to confront the complex realities behind highlighting these individuals, some of whom are themselves ambiguous or potentially problematic (the aforementioned Garvey and, in this series, Derek Walcott).

The exhibition covers two projects that Strachan has named for the theme of invisibility. Both hammer home the realisation that many of the figures he reminds us about were well-known and successful in their time. However, they are being aloud to fade, to recede into history as whiter accounts paper over them.

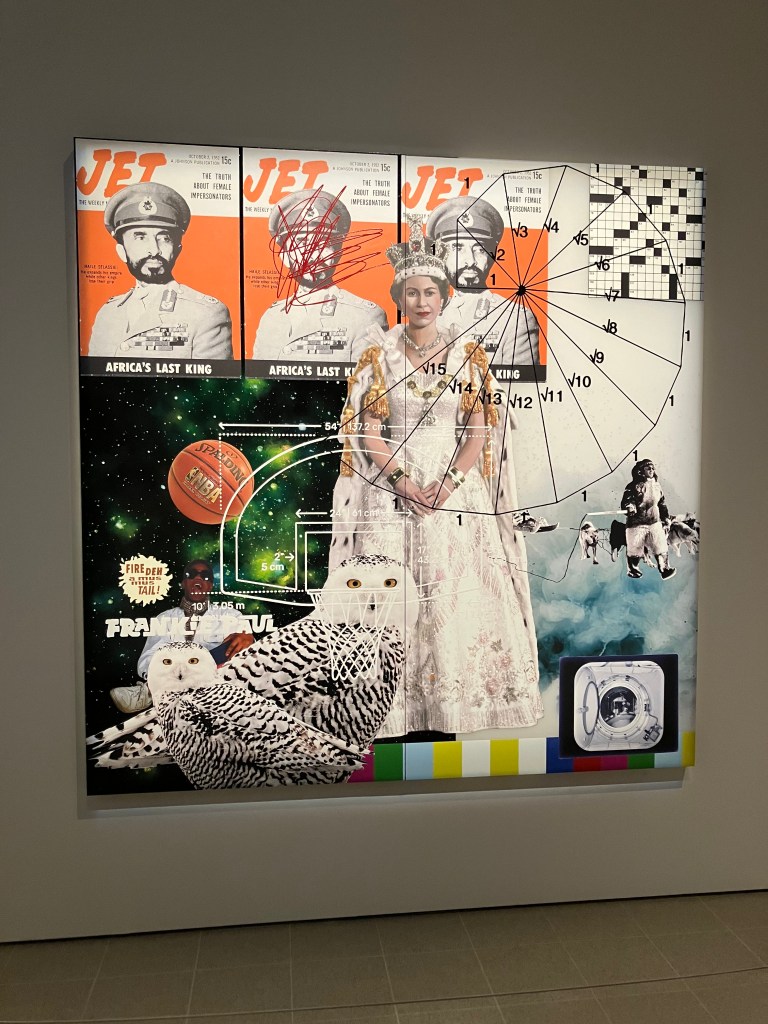

One of the ‘Invisibility Paintings’, called ‘Every Tongue Shall Confess’ features both Queen Elizabeth II and Haile Selassie I. As the accompanying text explains, the image alludes to the story that when the two met, the Queen bowed to Selassie, recognising that he, as Emperor of Ethopia, was of superior rank.

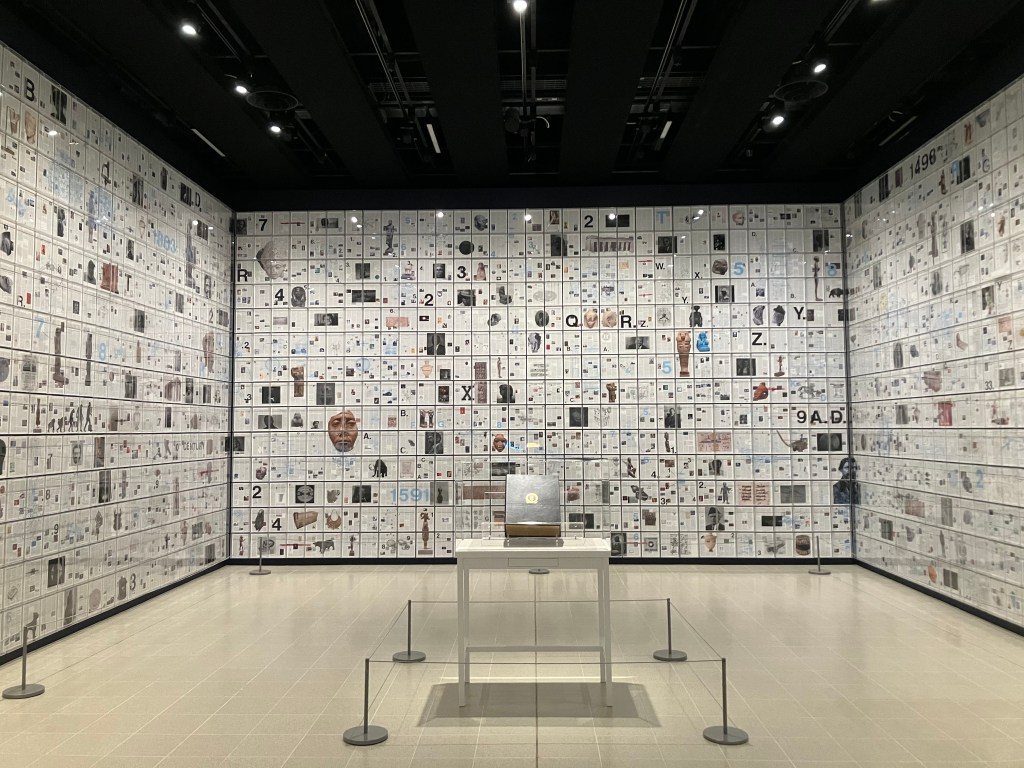

Whereas the ‘Encyclopedia of Invisibility’ – which in its glass case might look to the casual observer like a Britannica pastiche – is in fact a fully-realised feat of research, with over 2,000 pages of entries, a monument to Strachan’s unjustly forgotten pioneers. A vast selection of its contents are exploded across the surrounding walls of the room, constantly annotated, re-worked, even defaced, as if in preparation for infinite future editions.

In the past, I’ve often enjoyed exhibitions that coolly align with the Hayward’s vast, austere spaces, the recent Sugimoto retrospective being a key example. Instead, Strachan’s work seems to strain against this blankness, its size and colour fighting to breach the confinement, to remarkable effect.

For some of these conceptual works, we see only the relics in the gallery. The remains of the Bahamian Aerospace and Sea Exploration Center, for example, or photographs of Strachan emulating the achievement of Matthew Henson, the explorer who may have been the first individual to reach the North Pole.

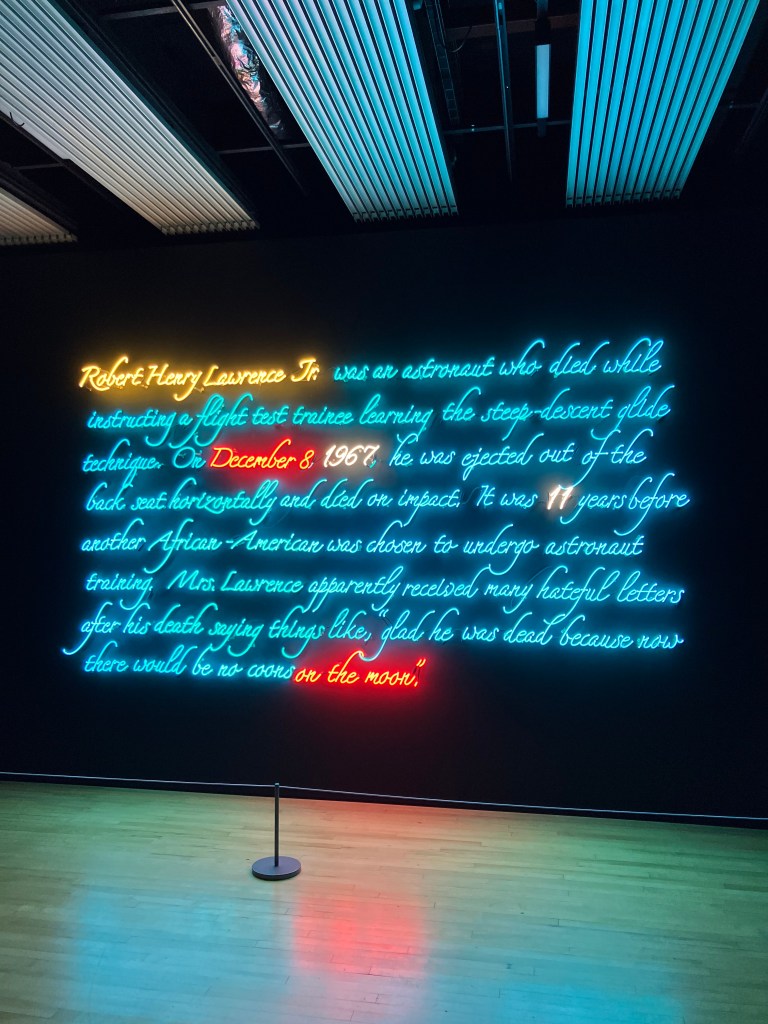

Strachan’s aspirational interest in travel and exploration is tempered by sadness and horror, as he examines the death in an accident of the first African-American astronaut, Robert Henry Lawrence Jr – which provoked hate-mail to his widow from racists celebrating the tragedy.

Strachan pulls the rug from under our feet by outlining this shameful incident In the same bright neon text that he used earlier in the exhibition to display the more dignified, hopeful words of James Baldwin that give the exhibition its name. Again, the artist calls out difficult, uncomfortable truths and gives them the same treatment as the joyous and celebratory.

Perhaps the most exhilarating example of how Strachan leaves behind the confines of the gallery is his sculpture of the SS Yarmouth (the flagship of the short-lived shipping company founded by Marcus Garvey, the Black Star Line). This Yarmouth floats proudly on the flooded terrace of the Hayward, tunes blasting out from a sound system hidden within, the banks of the Thames lining your field of vision in the background.

It’s a soaring expression of escape and elation, disappointment and displacement: a perfect summing up of this unpredictable, and ultimately uplifting exhibition.

AA

This exhibition continues until 1 September at the Hayward Gallery on London’s Southbank.

Exhibition photos by AA.

Discover more from ARTMUSELONDON

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.