John Le Carré insisted that he was a writer first, and sometime spy second – and this excellent exhibition drawn from the author’s archive honours that self-image. It’s easy to emerge from the exit thinking Le Carré was half man, half words but – appropriately enough – the reality is not so simple.

The entrance to the display is rather on-brand: a doorway at the far end of the Weston Library’s vast foyer, identified by as much illumination as furtive modesty will allow. Once inside, the hang connects instantly with the visitor. Glass cases systematically focusing on aspects of Le Carré’s life and career, or highlighting individual novels for which the archival content seems especially strong: it’s all irresistible for any book enthusiast and aficionados of spy fiction in particular will think they’ve died and gone to some murky, morally-compromised heaven.

The title ‘Tradecraft’ is well-chosen. A typically bland term used to describe the practical techniques of espionage, it doubles neatly here as a suggestion for how Le Carré viewed his approach to his writing – methodical, meticulous, with source material, contacts and layers of research underpinning the final, gripping results.

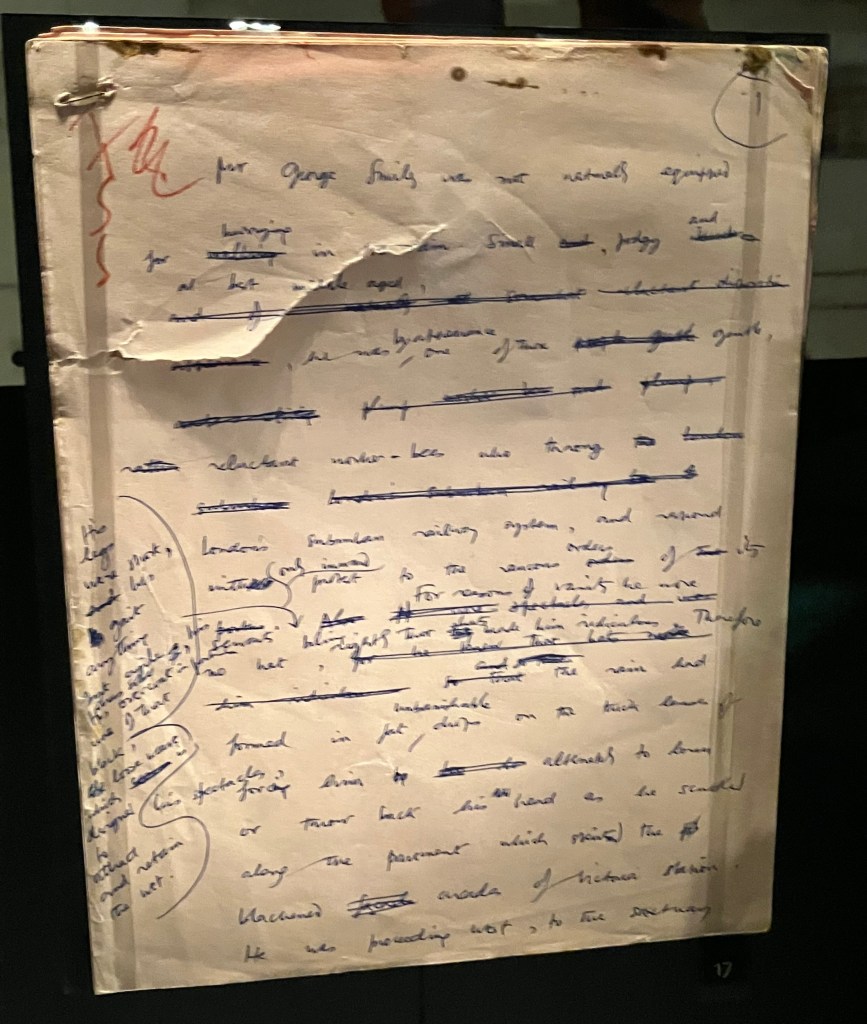

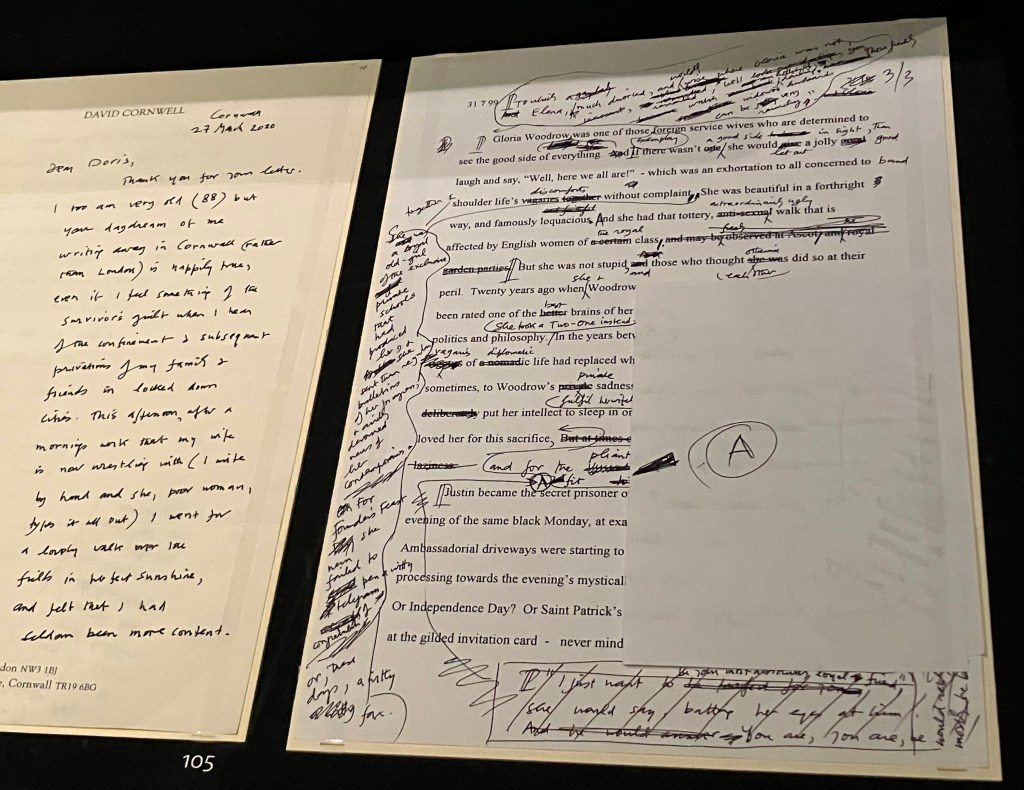

Accordingly, there is a major focus on Le Carré’s actual writing: longhand and lots of it – letters, annotations, notebooks and even – in one of my favourite of all the exhibits – a plot outline (‘The Little Drummer Girl’) in diagram form. It’s a comfort, and encouragement, that even this most sophisticated of storytellers, whose remarkable gifts for plotting and characterisation were as unknowable to me as the clandestine activities he wrote about, still put himself through extensive mindmapping processes and ceaseless revisions. As great musicians tell you, however mystically gifted your favourite artists may seem, practice is still the key.

The curation finds the right balance of popular and niche appeal. Fully aware that many fans will associate Le Carré as much with the celebrated adaptations of his work as with the original novels, it gives appropriate space to film and television ephemera, while always filling in the biographical and literary gaps. No surprise, then, at the focus on recent TV hit ‘The Night Manager’, or – looking further back – Alec Guinness’s unforgettable incarnation of George Smiley in ‘Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy’ and ‘Smiley’s People’ for BBC TV.

We marvel at a letter the actor wrote to Le Carré expressing reservations about playing the role, surely one of the greatest casting decisions in broadcast history. But it’s as thrilling to see Le Carré’s own handwritten sketch of the Smiley character nearby.

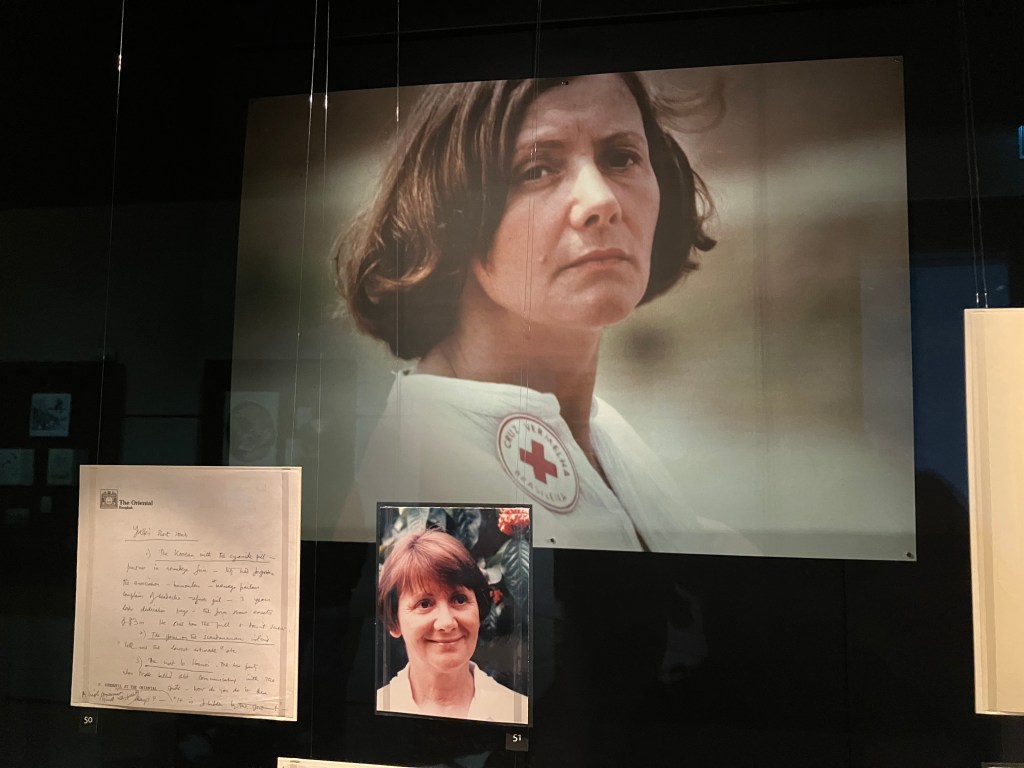

I was particularly pleased to see a display on ‘The Constant Gardener’, which became a fine film starring Ralph Fiennes and Rachel Weisz. A story of corruption in the pharmaceutical industry, the exhibits pay photographic tribute to the humanitarian worker who inspired the novel, Yvette Pierpaoli, along with Le Carré’s diligent notes of her recollections, and his furious letter to two of Novartis’s legal team who called the integrity of the book into question. However hard-nosed these lawyers may have been, one likes to think it was a bad day in the office when Le Carré’s missive – a somehow calm and correct dismissal that still burns with disdain and disgust – landed in the in-tray.

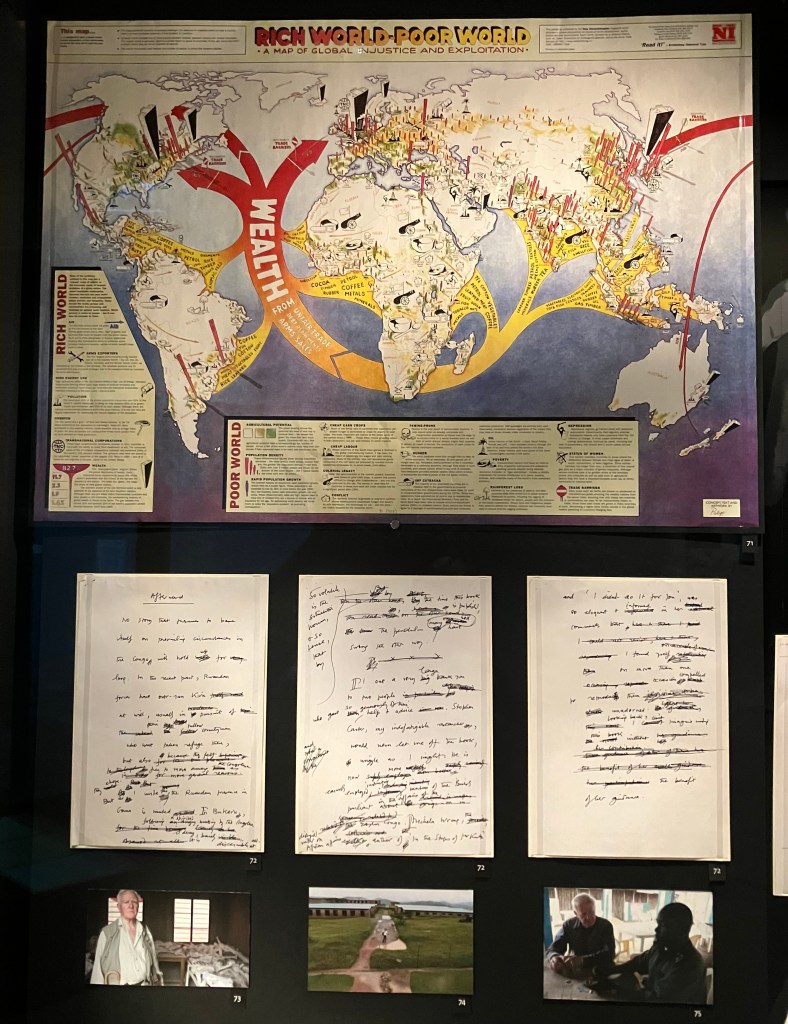

However, while readers may feel an obvious ‘blockbuster’ or two is missing, it was refreshing to see some of the more unusual titles emerge from the shadows – such as ‘Our Kind of Traitor’, ‘A Most Wanted Man’ and, below, ‘The Mission Song’.

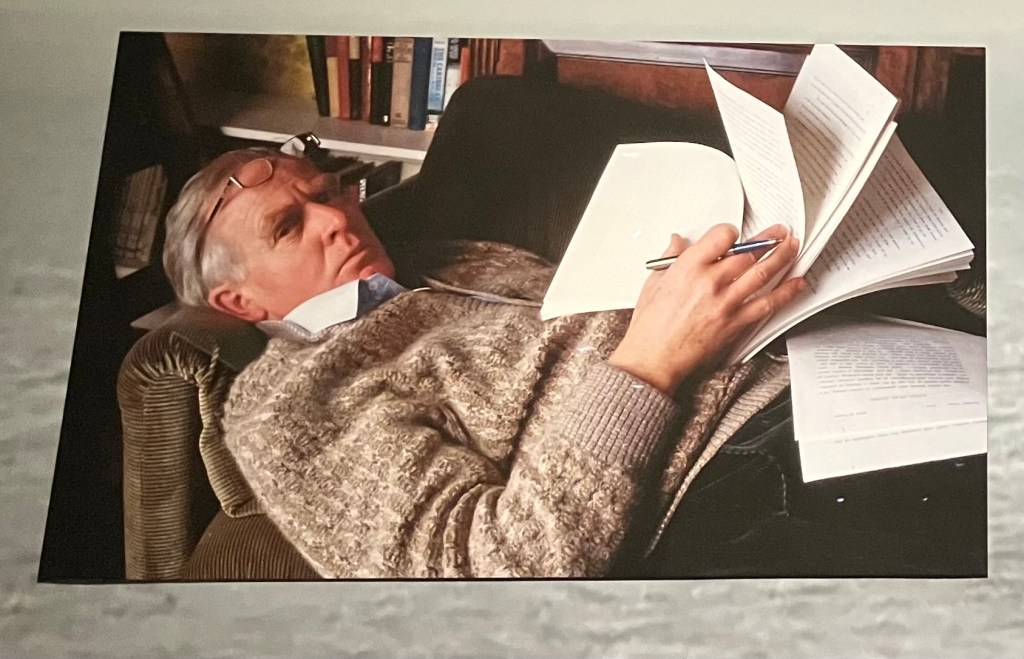

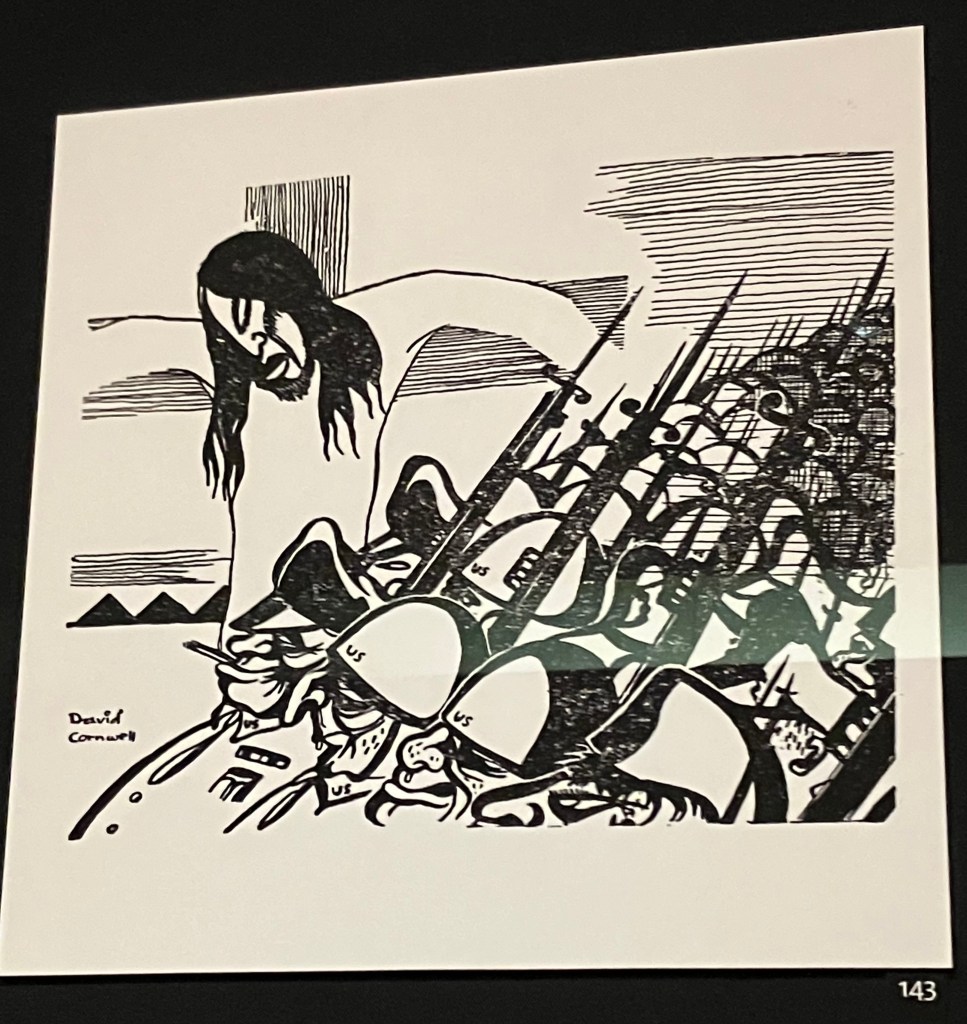

Perhaps even less expected are the spotlight given to Le Carré’s talent for illustration, and the photographs of him at work, pen permanently in hand, whether on location or on the sofa. Both paint a picture of this compulsive observer and chronicler, driven to bring dark truths to light.

We can also see a list – amusing but slightly chilling at the same time – of terms and phrases he coined to colour his characters’ language. The department is famously ‘the Circus’, surveillance experts ‘lamplighters’ and agents skilled at following targets unnoticed ‘pavement artists’. Words attributed to Le Carré have entered the language of spycraft, bringing the author back into espionage in a way he might not have predicted.

There is one area of Le Carré’s compulsiveness that the exhibition necessarily leaves shaded: the relatively recent reports of his serial adultery. Given the nature of the archive, much of ‘Tradecraft’ is the Le Carré perspective. As Blake Morrison summarises in his Guardian review of (author’s son) Tim Cornwell’s edition of Le Carré’s letters, correspondence that would have shed more light on this particular dark side of the author has been lost. There will always, it seems, be some secrets left.

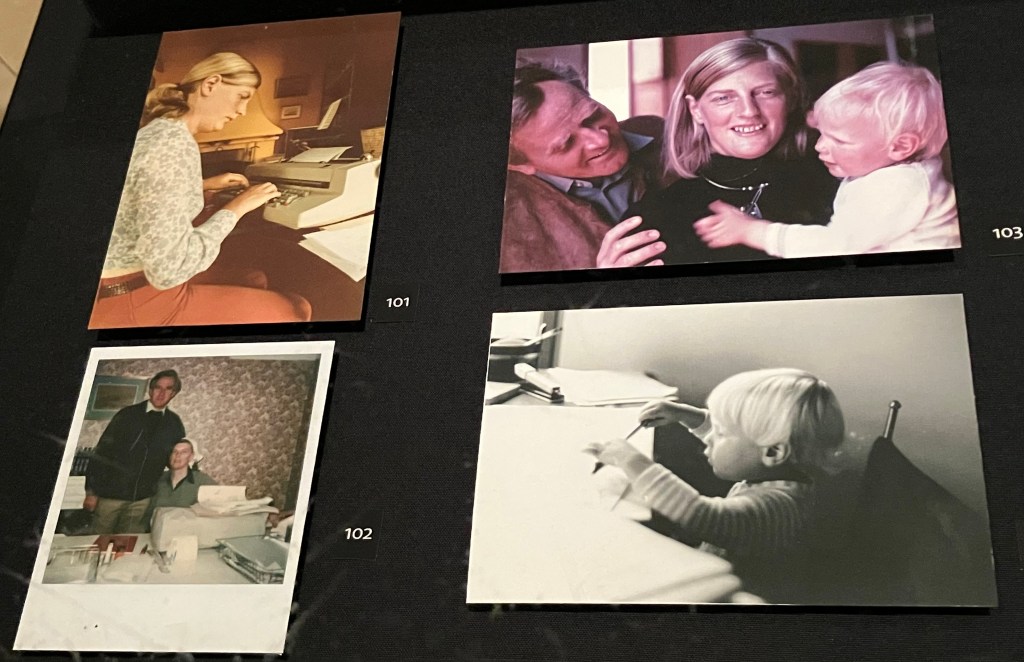

In these circumstances, the exhibition’s handing of Le Carré’s personal life is rather deft, foregrounding the unique part his wife Jane – a publishing executive – played in his career, acting as typist, copy editor, administrator: an indispensable collaborator and supporter of his writing. I have no wish to romanticise or over-complicate the actions of a philanderer, but perhaps there is evidence here of love as a man like Le Carré might have understood it – not so much in his admiring comments about Jane, but in their shared system of corrections and mark-ups, and her intuitive understanding of his work.

Recommended, by hushed word of mouth.

AA

’John Le Carré: Tradecraft’ runs until 6 April 2026. Admission is free.

Discover more from ARTMUSELONDON

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.