‘7 Deaths of Maria Callas’ is described as an “opera project”, the brainchild of performance artist Marina Abramović. The timing is ideal – English National Opera (ENO) describes the piece as “celebratory”, as we approach the centenary of Callas’s birth on 2 December; while Abramović is currently the subject of a major retrospective at the Royal Academy of Arts. I was intrigued to find out how one artist would pay homage to the other.

If, indeed, that’s what actually happened: I am not so sure. And that is one of the reasons I really enjoyed it.

The show does not have a conventional plot in the way you would normally expect from an opera. For most of the running time, Abramović is silent and motionless, lying in a bed close to the wing – it will later emerge that this is Callas’s bed, in the Paris hotel room where she died.

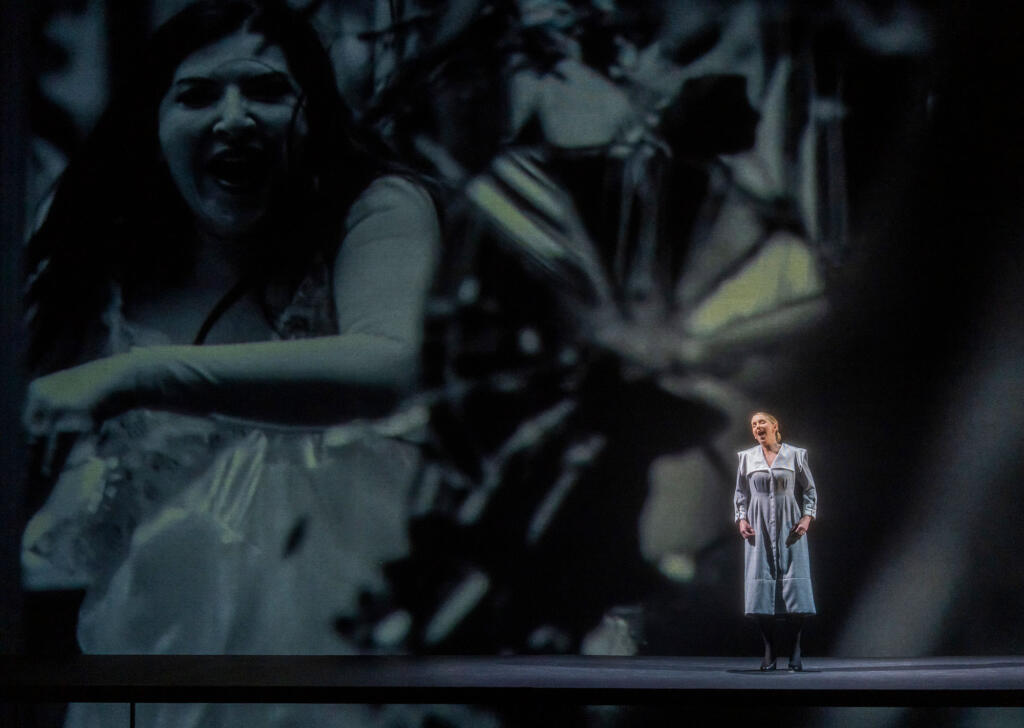

Seven sopranos appear in turn, performing seven arias from seven different operas. Each aria is the final one sung by the opera’s heroine before she meets an untimely end. However, there is no attempt to transform the soloists’ appearances into either Callas, or the relevant character. Instead, they all appear in relatively dim light, in a similar nondescript plain dress.

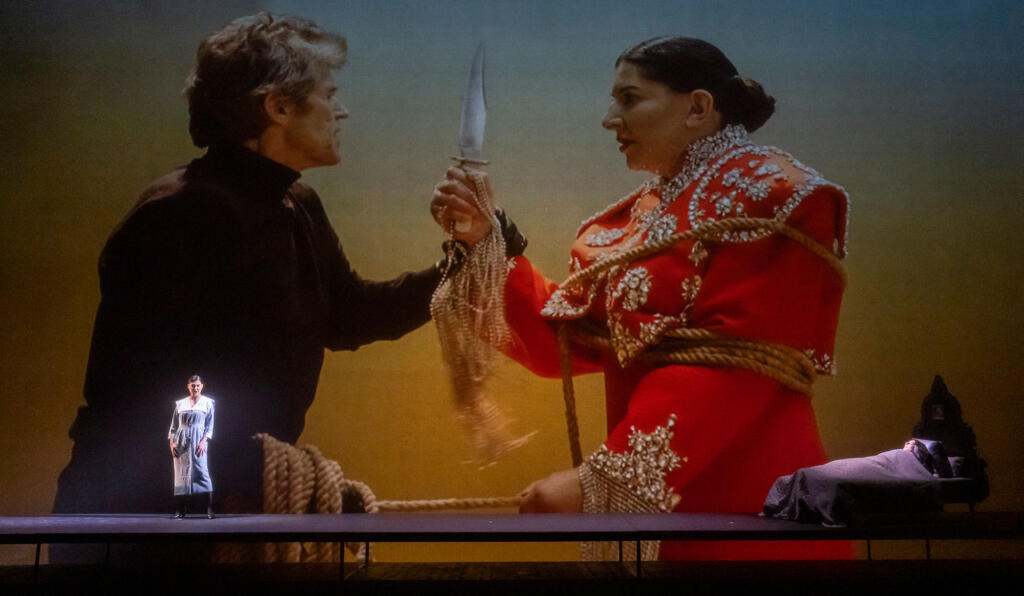

At first, the reason for this seems purely practical, to minimise distraction from the main visuals. During each aria, a short film is projected across the vast width of the Coliseum stage. Abramović co-stars in these vignettes with the actor Willem Defoe. The pair silently enact what are essentially Abramović’s riffs on each heroine’s death scene – more on this later. Before each segment, weather patterns on the screen accompany the artist’s recorded voice speaking specially-written “lyrics” against more abstract, electro-orchestral musical links.

After the seventh aria, there is a pause, then a complete change. The screen is raised, the set lit and we see the full Paris hotel room for the first time. Abramović stirs, slowly ‘wakes’ and comes to life. There’s a sonic transformation, too, as the women of the ENO Chorus appear in boxes both sides of the stage and perform a haunting, choral outro. Abramović exits the suite and a group of maids appear to clean and ‘shut down’ the room – we soon recognise them as the seven soloists in their bland uniforms.

In the closing moments, Abramović reappears in full concert dress, while a recording of Callas as Tosca plays faintly in the background. This is the first time we have heard her voice all evening. Blackout cuts her off mid-aria.

*

I am sure this piece will divide audiences. It can be accused of messing with operagoers’ expectations. There is no significant characterisation or realisation of Callas herself, and the crack team of sopranos are not given any dramatic opportunities to speak of. So it risks disappointing those seeking ‘actual’ opera.

But these decisions seem sound and deliberate to me. I felt the absence of Callas more keenly than I would have felt her presence. The project does Callas the honour of openly acknowledging her uniqueness. Imitating or impersonating her vocally would only have diluted her ghost’s power; and even visually, Abramović evokes Callas directly with great care. I was moved by her closing gestures during the Callas recording; while acknowledging her public in character, she pointedly did not mime to the recording, but kept a fixed smile on her face, lips tightly shut. She was not going to tread on Callas’s territory. The abrupt halt to proceedings conveyed the untimely end of Callas herself, taken at only 53.

And while it might sound like the soloists were sidelined in some way, that wasn’t the reality. While the filmed sections filled our vision, the sopranos took on a kind of ‘spectral accompanist’ role. Each miniature movie was in slow-motion, drawing out its concept to near breaking point – so instead of assaulting the senses with information overload, we had plenty of time to absorb both sound and vision. As a result, the beauty of each accompanying aria was emphasised in a way that felt quite distinct from their impact as part of a dramatic narrative; and each singer was free to give her own take on the character free of ‘normal’ costume or production constraints.

I also believe that anonymising and standardising the appearance of the soloists – especially in the form of maids, representing subservience – is a key metaphor in the whole piece. Misogyny in opera has often, rightfully, been discussed: so many of its women characters are there to suffer – but this also translates into great parts that sopranos (more often than not) want to sing. As such, artists can embrace the problematic elements of opera, rather than dismiss or ‘cancel’ them.

Accordingly, Abramović charges into this area head-on. Despite the beautiful music from a range of composers telling a variety of stories, here the heroines are divorced from their original narrative setting and defined solely in terms of their imminent deaths, one inevitable demise after another.

The films expand this idea further. The slow-motion technique seems to satirise the clichéd ‘drawn-out’ death – what takes an instant in the real world lasts for an aria in opera. (My only real criticism of the visuals is that I felt the sky projections were a bit on the nose: ‘this is a voice from the beyond!’) But something else struck me about some of Abramović’s interpretations – the updates seem broadly relevant to Callas herself, or the period of time when she was dying. For example, Butterfly is shown exposing herself to radiation in front of a returning Pinkerton in a barren, post-nuclear landscape – surely a reference to the US bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Othello ‘smothers’ Desdemona not with a pillow, but by coiling a boa constrictor around her, as if Medea’s snakes were taking their revenge. Tosca, in the first clip, falls to her death from a stylised skyscraper (Callas was born in New York), into the roof of a mid-century motor car.

In the epilogue, this referencing is reversed, as the ‘walking’ Abramović/Callas appears to remember or relive certain elements of the film sequences (a walk to a high window, a shattered vase). This, along with the reappearance of the sopranos as maids, emphasises the idea that the Callas figure has woken from a classic ‘life passing before her eyes’ nightmare, portending her death. We’re reminded that Callas has rehearsed for death, over and over again, onstage for our entertainment.

I think the psychological impact of repeatedly enacting death, the potential for artistic suffering to spill over into offstage life and make the heroines’ torment ‘real’ – is perhaps what interests Abramović most about Callas. After all, this is consistent with key themes of Abramović’s past work, controversial due to her explorations of endurance, body horror and self-harm, to the point of personal risk. This project suggests she sees a close parallel between her own practice and the mental/physical extremes to which opera singers expose themselves. It would be absolutely correct, I’d say, to view the piece as being about Abramović rather than Callas, but that’s why it works. Callas is elusive, unknowable; but Abramović knows Abramović better than anyone.

Finally, it’s worth considering who this show might bring into the opera house. Seasoned operagoers are perhaps at most risk of feeling frustrated, given the ‘bitesize’ nature of the excerpts: but they can still enjoy the opportunity to hear a gorgeous ‘variety show’ of performances from Aigul Akhmetshina, Nadine Benjamin, Sophie Bevan, Elbenita Kajtazi, Eri Nakamura, Karah Son and Sarah Tynan – all in glorious form.

Those hovering on opera’s edges, however, might find a great deal to pique their interest. The presence of Willem Defoe (one of cinema’s most interesting faces, perfect for conveying the silent anguish or cruelty required of him here) and arresting use of visuals might lure in film buffs. The new linking music (by Marko Nikodijević) might intrigue fans of electronica and its interactions with classical/choral composition. And I would argue the piece is essential for anyone following Abramović’s work, or any kind of performance art where the practitioner looks inward to themselves as a subject. Guiding the curious towards this living playlist of Callas arias could result in a new cohort of future opera fans heading for the Coliseum’s exits, wondering what to see next.

AA

(All photos are by Tristram Kenton, from the ENO website production gallery.)

Discover more from ARTMUSELONDON

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.