Benjamin Britten’s opera, The Turn of the Screw, is a psychological thriller based on Henry James’s novella of the same title. In the world of opera, psychological thrillers are thin on the ground and for good reason – it is hard to express narrative ambiguity or uncertainty in musical theatre.

Isabella Bywater’s production at English National Opera last week showed to what extent staging could play a major part in telling a complex, multifaceted story.

Britten was obsessed with James’s novella, which he had read in his teens. Lost innocence or innocence in danger, is a recurrent theme in his music.

The core of this tense drama rests on a governess’s painful efforts to protect two parentless children from danger..

The plot cannot be reduced however to a fight between good and evil. What happens on stage is open to different interpretations. The Governess, it could be said, has her own version of events for example. She finds the children strange and deduces they have been corrupted by the recently defunct valet, Peter Quint who worked at the grand house they are living in. The old housekeeper has warned the Governess that Quint, when he was alive, was “too free” with Miles. The audience inevitably fears the worse. But is the Governess’s fear irrational? The young girl Flora believes her governess has lost her hold on reality. But the Governess is adamant she has seen Peter Quint’s ghost and that he has come back for Miles.

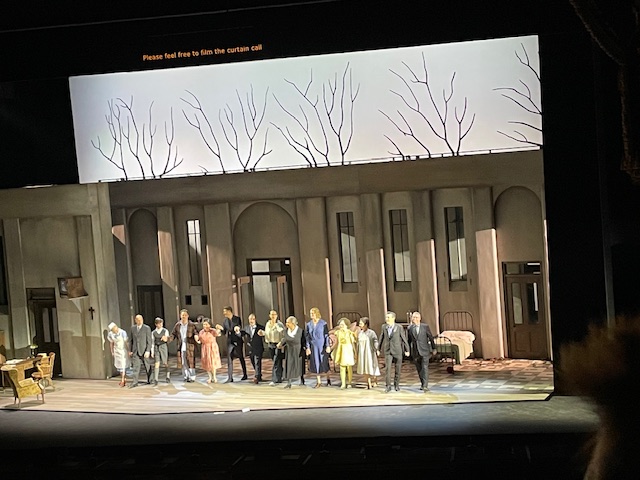

When I went to see the opera on opening night I was struck by the brilliance of the set which conveyed ambiguity so neatly.

Two buildings on stage, the hospital and the Bly estate, expressed the split in the Governess’s consciousness. She woke up in the hospital with nurses and a porter milling around her. The porter bore an eerie resemblance to child-molester Jimmy Saville. Having left her bed, the Governess stepped inside her other home, the school room of the stately home.

Good and evil is everywhere in the libretto. The Governess refers to the children as ‘strange’. The old housekeeper insists they are ‘good’. On the surface they do seem like any lone children with little company, who fill their day with school lessons (Latin plays a big part) playing games, singing nursery rhymes, singing in church.

The strangeness is deftly reproduced in Britten’s music writing. He’s a master at making normality go awry as lyrical melodies go askew with dissonance. Britten makes full use of the orchestra to create aggressive percussive effects. As the children sing Tom Tom the Piper’s Son it is delivered in a trance-like tone. A noisy militaristic snare drum takes over – everything seems to burst forth with raucousness. And most memorable and haunting is the aria Miles sings – it is incomprehensible to the audience and beautiful – Miles feels compelled to sing it without knowing why.

Ailish Tynan was magnificent as the anxious Governess – her awkward body posture said is all. It’s a demanding role, she is never off stage. Meanwhile Gweneth Ann Rand’s warm soprano conveyed the essence of the generous-minded housekeeper. Robert Murray, as Quint, had a tenor that was almost too beautiful to project evilness and Miles’s treble, sung by Jerry Louth, was most affecting and is running around my head as I write!

A riveting production at ENO – go before it comes off.

KH

The Turn of the Screw opened on Friday 11th October and continues for 7 performances more: Oct 16, 23,29, 31 at 19.00. Oct 13th at 14.30. October 26 at 18.00

Discover more from ARTMUSELONDON

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.