Before this recital, I’d only had relatively few opportunities to hear mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke live. The first occasion was Handel’s ‘Orlando’ in concert at London’s Barbican in 2016, an evening of such brilliance, I still think about it often. Cooke gave a memorable performance as Medoro (alongside other favourites of mine, including Iestyn Davies and Carolyn Sampson), and I made a mental note at the time to keep track of her recordings and watch out for other appearances. Perhaps even more vivid was her haunting interpretation of the lead role in Nico Muhly’s ‘Marnie’, at English National Opera.

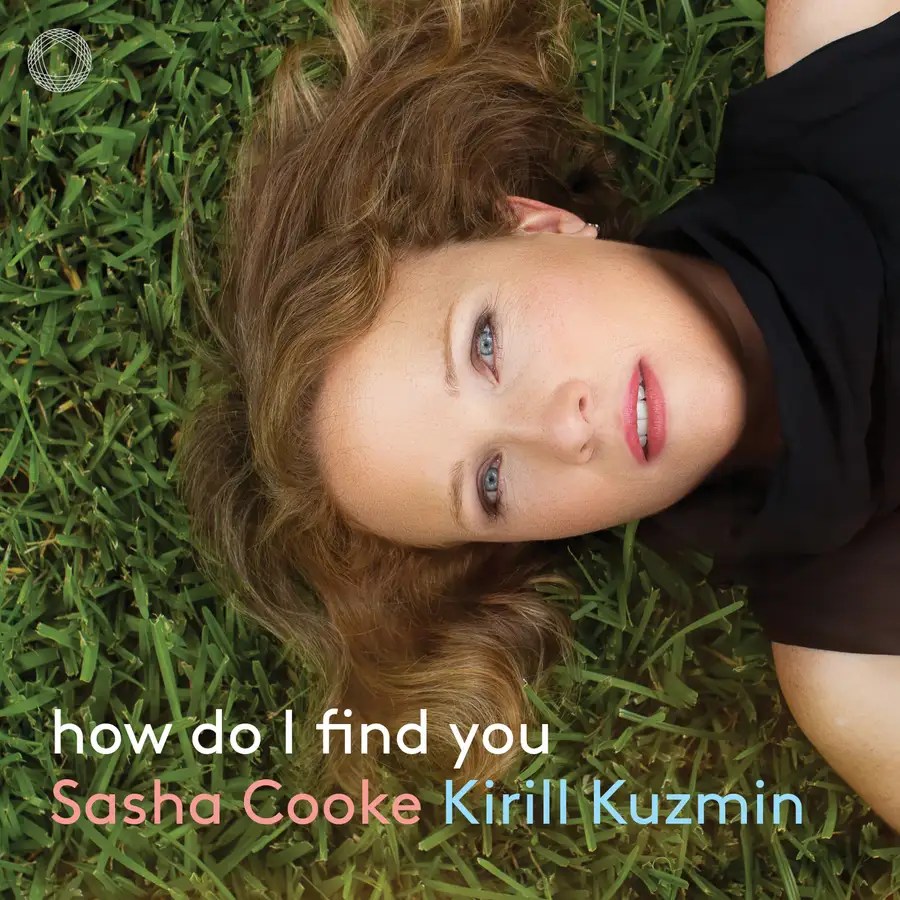

Cooke also created – and curated – one of my album highlights of 2022, ‘how do I find you’. Collaborating with pianist Kirill Kuzmin, she commissioned and recorded new songs from younger composers addressing the lockdown experience. The resulting programme succeeded in showcasing Cooke’s adventurous versatility with affecting emotional immediacy.

This open-access approach to such depth of feeling was crucial to this programme, ‘Love Letters’, which built towards the UK première of a three-song cycle by Scott Ordway, setting love poetry written by Cooke and her husband during their courtship. More of this later.

Overall, the recital revolved around themes of love, desire, yearning… but also, as the ‘Letters’ of the title imply, love as an ‘exchange’, or combination too; the mutual influence and intermingling of male/female aspects within a relationship, or even an individual.

For example, Cooke and Martineau began with Debussy’s ‘Chansons de Bilitis’, his popular settings of erotic verse – apparently by a woman poet from Sappho’s time, but in fact, the fictional creation of a man, Pierre Louÿs. This ambiguity – that such an evocative portrait in words and music of female sensuality is in fact the work of two blokes, utterly immersed in their respective idioms – provided a fascinating flipside to the closing Ordway pieces.

We were then invited to compare songs by Alma and Gustav Mahler. Again, the choices made by Cooke and Martineau revel in nuance. At first, they foreground Alma over Gustav – and quite right too, given his insistence ahead of their marriage that she stop composing. Her innovative writing style and penchant for setting modern, at times conversational, texts make a sharp contrast with his heritage-bound folk-poetry focus. But the repertoire avoids over-simplifying the narrative. We heard three ‘love songs’ by Gustav which pre-date his relationship with Alma, and which reveal a kind of modest, almost spontaneous response to the source material. Take the innate humour in ‘Verlorne Müh’ (‘Wasted effort’), and especially the striking sparseness of ‘Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen’ (‘Where the splendid trumpets sound’).

To begin the second half of the programme, Cooke sang indirectly of forbidden love. Wagner’s ‘Wesendonck Lieder’ illustrates the bond (creative and personal) between composer and poet: two of the songs anticipate perhaps Wagner’s ultimate outlet for his illicit ardour, ‘Tristan und Isolde’, and the whole cycle seems to embody a consummation of their respective, ardent approaches to their art.

(I also think it speaks to the recital’s themes that, on each side of the interval, we saw how you could still home in on the core of a ‘colossus’ – still get a sense of their inner being – by looking at their miniatures, as much as the gargantuan works for which they are best known.)

Perhaps my favourite part of the concert, however, was the closing ‘Expanse of my Soul’, three songs composed by Scott Ordway using lines from love poems exchanged between Cooke and her husband, Kelly Markgraf. Ordway took the inspired decision to set two of the pieces with both ‘voices’ in correspondence (the third happens to contain words by Cooke alone). As a result, everything about the cycle is testament to how ‘in tune’ with each other the couple are. The occasional, slightly rawer phrase might betray some of Markgraf’s verse compared with Cooke’s allusive reach, but it’s the shared characteristics that so powerfully depict two halves of a partnership moving towards the same ‘beat’: similar line lengths, mantra-like rhythms and a shared response to nature – water, sun and sand.

No doubt with a nod to the requirement for mezzos to ‘wear the trousers’ in certain roles, Ordway brings out Cooke’s range but avoids a simple ‘low notes = man, high notes = woman’ code: instead, the ambiguity is preserved, Cooke’s warm, rich tones bringing both parts of the equation together, a true musical portrait of two souls coming together as one.

At the start of the concert, the Bilitis songs felt rooted in what you might call a ‘sincere deception’, a desire to create something beautiful that had no foundation in reality. At the close, however, ‘Expanse of my Soul’ offers three songs pointing to a different way of exploring male/female boundaries and connections, based on honesty, openness and truth.

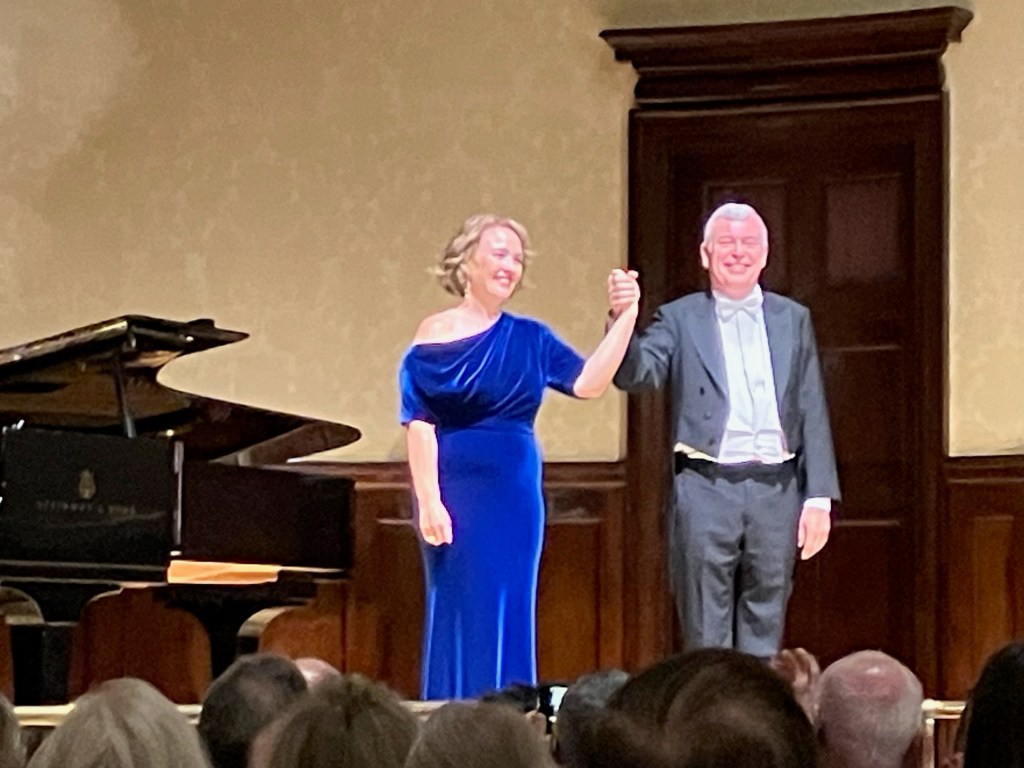

Those three words could easily be used to describe Cooke’s performance throughout the evening. She was in glorious voice – such a warm, generous sound, conveying a miracle-blend of both lightness and gravitas, an overall sense of grace. Her acting and movement were also finely-judged, inhabiting these songs’ protagonists in a way that fully engaged, until the closing moments when no artifice would be expected or required. Martineau was an impeccable collaborator, somehow – as ever – playing the piano as if in character, supporting every shift in tone or mood.

I hope it’s not long before I have the chance to hear Sasha Cooke perform again.

AA

Discover more from ARTMUSELONDON

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.