‘Madame Yevonde’ (born Yevonde Philone Cumbers) was a professional photographer whose versatile, pioneering career – lasting some 60 years until her death in 1975 at the age of 82 – reflected the relentless pace of change during the twentieth century.

When visiting this major exhibition devoted to her work, it feels like walking through several parallel histories.

Social: women’s rights and their representation – figuratively and literally – through Yevonde’s lens.

Technical: the advent of colour processing and Yevonde’s role in legitimising and popularising the dramatic results.

Artistic: the wit and elegance of Yevonde’s use of motifs from other fields (graphic design, still life, surrealism) while retaining her own aesthetic style and commercial sense.

Yevonde decided to take photographs for a living more or less the second she started using a camera – and the exhibition’s early stages suggest the arrival of a complex, fully-formed talent. The first part of the hang shows her society portraits already dovetailing with her sense of humour and drive to innovate and experiment.

When the new ‘Vivex’ process made colour accessible to working photographers, Yevonde immediately embraced its potential (while many of her contemporaries resisted). It brought both advantages and challenges.

On the plus side, fashion and society photography could demonstrate characteristics and nuances of fabric, make-up, and shades of hair and skin like never before. However, precisely because the colour format could offer the view so much ‘more’ to look at, Yevonde recognised that her creativity and imagination would need to keep pace with the scientific advances.

Yevonde had a particular penchant for the colour red. Seeing so many ‘red’ photographs together like this neatly encapsulates the wide range of themes that Yevonde was able to wrap into her own style and preferences. The portraits of actresses Joan Maude and Vivien Leigh may appear relatively conventional at first glance. However, Yevonde deploys Maude – and her vibrant auburn hair in particular – to help create a symphony of different, almost clashing reds with her surroundings. In the case of Leigh, Yevonde provides the red surround to pre-figure (the interpretation suggests) her imminent appearance as Scarlett in ‘Gone with the Wind’.

It also seems to me that the vibrant red lipstick in particular, worn by so many of Yevonde’s women – along with her general palette – must have anticipated the colour films of Powell and Pressburger, who seemed to share a similar shady obsession: take Moira Shearer’s ‘Red Shoes’, or the startling transformation of Kathleen Byron’s Sister Ruth in ‘Black Narcissus’.

The two other ‘red’ portraits displayed here are a remarkable contrast. The study of the ‘Newspaper Girls’ shows them as almost absorbed into their occupation, themselves newsworthy: they are red and black in the same way as the typefaces they pose against.

The image of racing driver and pilot Jill Scott – in trademark red, natch – might show the subject in a rare moment of stillness, but everything about the composition suggests imminent movement, from Scott’s coiled, almost aerodynamic pose to the horizontal blur of the background.

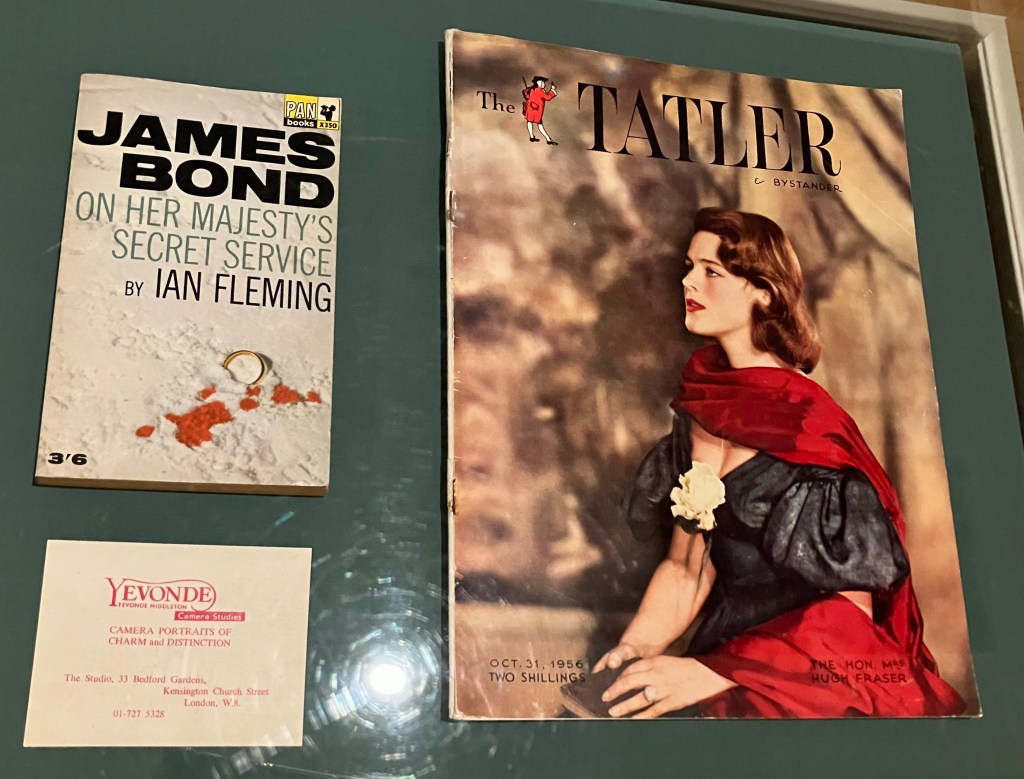

(Later in the exhibition, we see one of Yevonde’s most powerful uses of red on her James Bond cover illustration for Pan. Should they have included a spoiler alert?)

Innovative and unusual framing recurs through the work, meaning that its vibrant energy comes from more than just the colour. The exhibition gives major space to Yevonde’s most celebrated project, gathering what must’ve been almost the entire female attendance of a particular charity event and depicting them as mythological women or goddesses. I’ve highlighted two of my favourites but the show places the whole ‘galaxy’ of stars before you.

Later, heavily stylised, black & white portraits of Judi Dench and Marcel Marceau also seem snapshots of movement. Dench in particular appears to stretch further and further towards something beyond the border of the image. The solarisation technique also gives the mid-antics Marceau an outlined edge, making him appear even more like an illustration, a drawn character come to life.

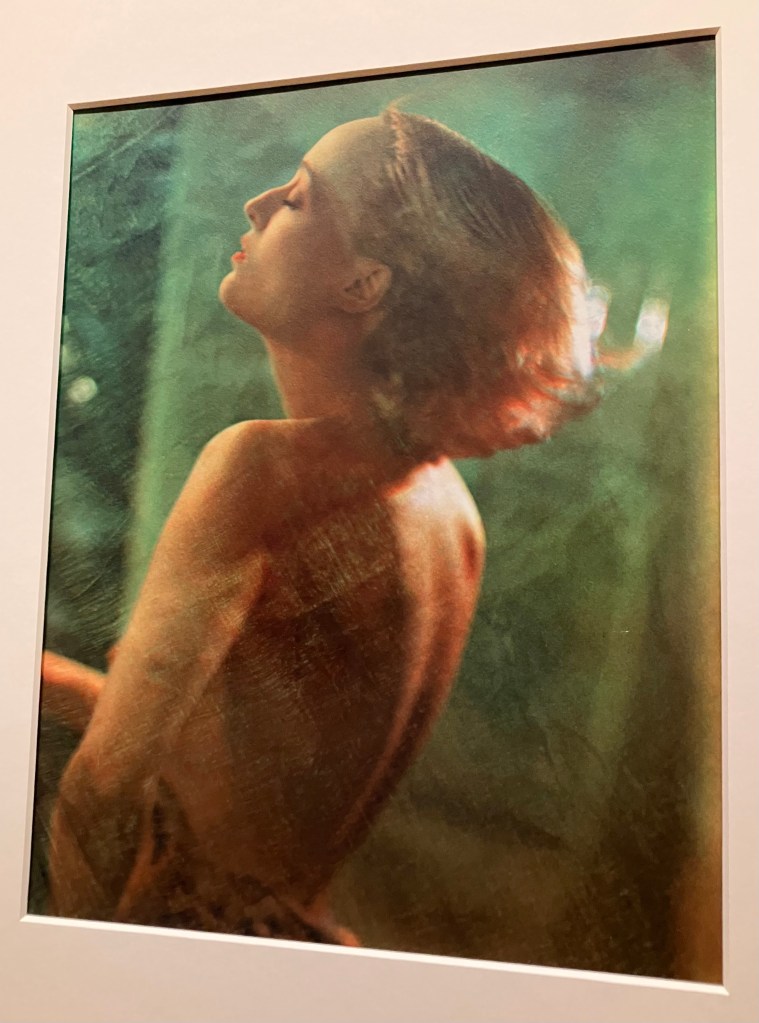

A lifelong advocate of women’s rights, with a history in the suffragette movement and women’s land army, Yevonde created a highly individual visual universe. She ‘understood the assignment’ of her profession – that glamour, attraction and allure were vital to draw both men and women to her photographs – and yet the women in her pictures are almost always shown to be powerful, in control: achievers, success stories, pioneers in the way she was. Where she might have strayed into areas of more passivity – nude studies, for instance – she took the opportunity to use an experimental treatment or format that made the portrait into something more.

As she began to incorporate other artistic movements into her style – especially surrealism and still lifes, often together in the same image – she nonetheless kept a gifted portraitist’s eye. Even the lobster broadcasts its personality as it stretches down the frame. It’s also worth noting her ability to draw out character from even inanimate heads, whether playful (cigarette) or – with war looming – poignant (gas mask).

I hope these photos have given you a feel for the exhilarating breadth of Yevonde’s career, supported by the NPG’s atmospheric hang. Please go and see her groundbreaking work for yourself, if you can. The exhibition is open until 15 October.

AA

(words and pictures)

Discover more from ARTMUSELONDON

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.