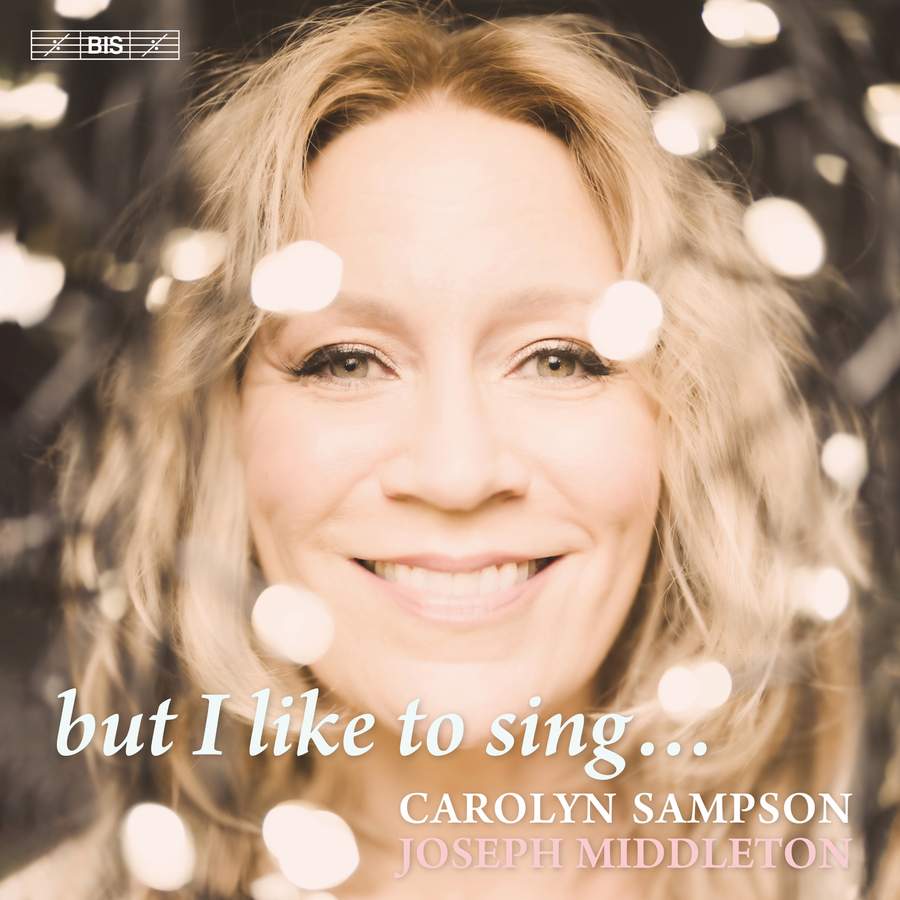

As many of you will know, soprano Carolyn Sampson reached her 100th recording as a soloist with the release of ‘but I like to sing…’ in November.

She celebrated this achievement online, with a series of short videos explaining some of the background to each recording. Full of relaxed charm – with an extra layer of addictiveness provided by Sampson’s daughter (stylist, director and, surely, future auteur) and crew – the series adds up to an informal, yet informative guide to Sampson’s entire career. (You can find these videos on TikTok, Instagram or X/Twitter.)

A casual glance at her catalogue might indicate a broad direction of travel from Baroque specialism to art song, but in fact, Sampson carries every strand of her experience with her, in parallel. Browsing the 100 releases chronologically brings to light surprises, the unexpected detours along the way – early forays into Stravinsky or Ešenvalds, for example – or cameo appearances on colleagues’ albums.

Some of the runs and juxtapositions drive home this range: take #61 to #64 – Sampson’s stunning performance in Poulenc’s ‘Stabat Mater’ was immediately followed by ‘A French Baroque Diva’, her extraordinary album with Ex Cathedra paying homage to celebrated 18th-century singer Marie Fel. Then, after the Mass in B Minor with regular collaborators Bach Collegium Japan, came ‘Fleurs’, her first art song recital album with pianist Joseph Middleton.

This gives a real sense of someone determining to explore her voice and follow wherever it takes them. Something intangible, a kind of gear change, seems to underly the second half of the ‘countdown’. Without neglecting those Baroque roots (plenty of Purcell to enjoy in recent years, for example), there’s an ‘all bets are off’ feel in the journey’s later stages. It’s been thrilling to follow Sampson’s recording career and discover so much music, programmed so thoughtfully and performed with such compassion, clarity and care.

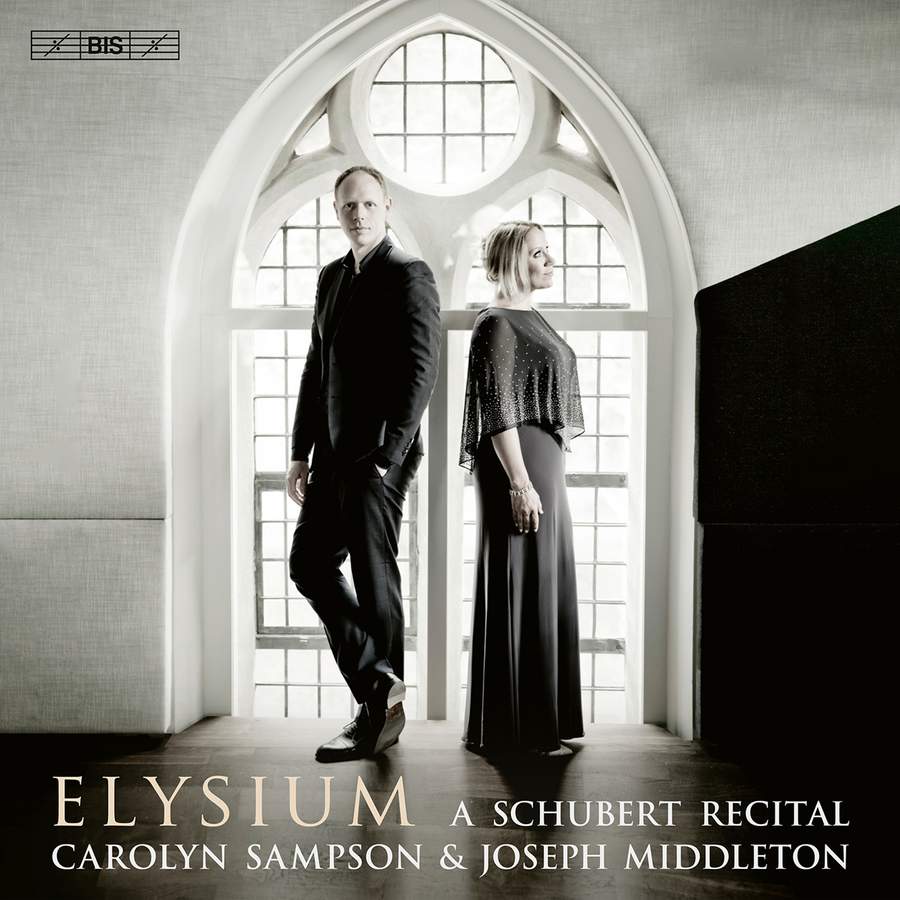

Partly due, no doubt, to unpredictable recording/release schedules, Sampson has been particularly prolific on disc in 2023. Back in March, her second album of Schubert songs with Middleton, ‘Elysium’, conjured up the ethereal paradise suggested by its title, with sublime versions of ‘Nacht und Träume’, ‘Litanei auf das Fest Allerseelen’ and an especially breathtaking ‘Du bist die Ruh’.

Even where the pace picks up, the same gliding, caressing delicacy applies: the duo’s near-telepathic rapport especially evident in a track like ‘Auf dem Wasser du zingen’, where they navigate subtle tempo changes to make the song ‘sway’ even beyond the ripples written into the accompaniment – or the gently propulsive ‘Die Sterne’, its restraint suggesting a confidence shared with the listener.

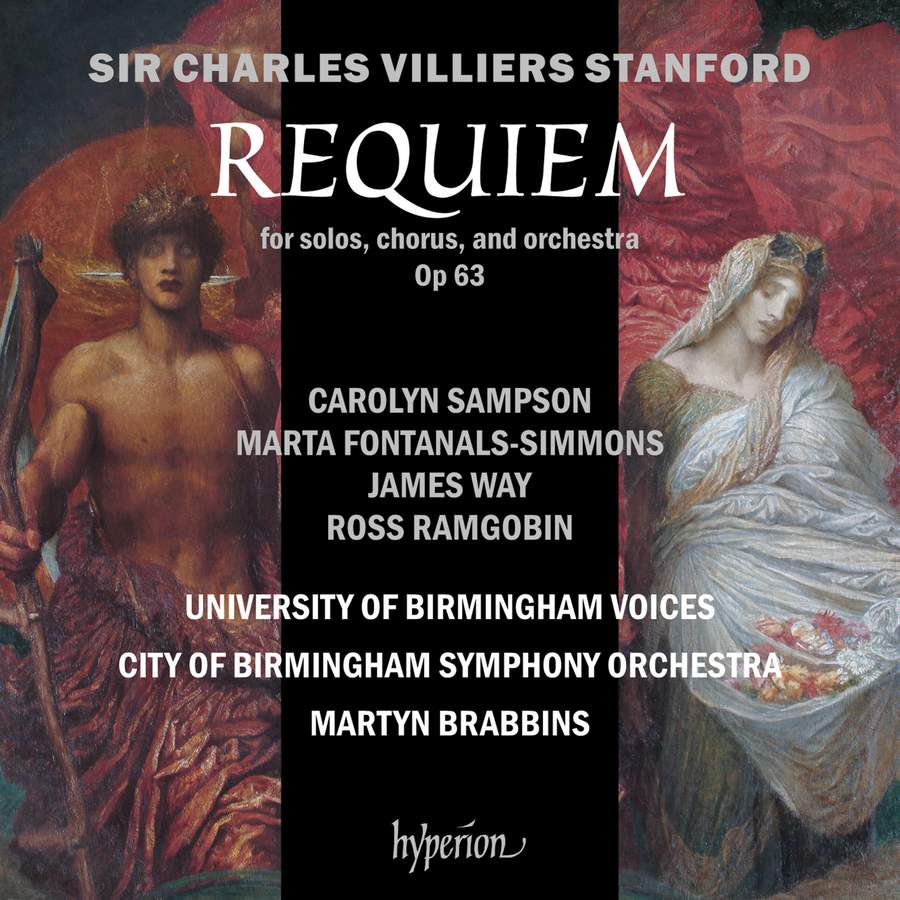

In May, Hyperion executed a ‘double Sampson’, issuing two releases featuring the soprano on the same day. Stanford’s ‘Requiem’, recorded with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra under Martyn Brabbins, was completely new to me – epic and moving, it’s hard to imagine better advocates for the piece than this formidable group of soloists (Sampson, Marta Fontanals-Simmons, James Way and Ross Ramgobin) with the University of Birmingham Voices.

Sampson also guested on the latest disc in harpsichordist Mahan Esfahani’s ongoing series of Bach keyboard works. The ‘Notebooks for Anna Magdalena’ – manuscripts gifted by the composer to his wife – include vocal and solo instrumental pieces, miniatures that contain multitudes. I had the pleasure of hearing Esfahani and Sampson perform this repertoire live at the Three Choirs festival in Gloucester and wrote about both disc and recital here.

The next release saw Sampson and Middleton bring Roderick Williams into the fold for ‘Sounds and Sweet Airs’, a Shakespeare-themed disc borne partly out of live programmes the trio had assembled exploring spontaneous, interactive ‘jukebox’ performances and ‘gender-swapping’ in art song. The pandemic derailed some of their plans, but anyone who was there will remember fondly their marathon Leeds Lieder concert working through these concepts in front of a rapt audience.

Sampson and Middleton normally build their duo releases around a theme, enabling them to highlight relatively unsung (literally) works alongside better-known repertoire. ‘Sounds and Sweet Airs’ is packed to its outer edge with 28 composers across 85 minutes of music. It also has one of the greatest record sleeves of all time.

A classic example of their programming flair, the disc is presented as five ‘acts’ with prologue and epilogue, using Shakespeare as the basis (a ‘springbard’, if you will? Blame the sherry) for featuring songs from home and abroad, then to now. The play template, along with the careful division of labour between Sampson and Williams, gives the recital both unity and variety. Discoveries for me among Sampson’s selections include ‘Arise’, a Castelnuovo-Tedesco setting from ‘Cymbeline’ that moves imperceptibly from a gossamer lilt to a sensual descending line, and Coleridge-Taylor’s ‘The Willow Song’, Sampson drawing out its dark, bluesy melancholy. (Favourite turns from Williams: the disarming, unpredictable Tippett settings from ‘The Tempest’, and Madeleine Dring’s lament ‘Take, o take those lips away’ from ‘Measure for Measure’, showcasing his rich baritone’s agility and tenderness.)

Sampson has often chosen to foreground the female perspective in earlier art song CDs (‘A Soprano’s Schubertiade’, ‘Reason in Madness’, ‘Album für die Frau’) and the Shakespeare project is no different. Its scope and ambition allows representation for women composers: songs by Dring and Amy Beach are joined by contemporary work from Cheryl Frances-Hoad and Hannah Kendall. The suite of songs by Kendall, ‘Rosalind’, was originally commissioned for the Leeds concert. Its startling soundworld, requiring Sampson to play harmonica and operate music-boxes, and drawing on Middleton’s ability to build a solid foundation from fractured parts, leads Sampson and Williams to explore the gender identity/fluidity theme by sharing Sabrina Mahfouz’s fascinating text.

Both ‘Rosalind’ and a new cycle premiered at Gloucester with Esfahani, Nilufar Habibian’s ‘Az nahāyate tāriki’ (‘From the deep end of darkness’), as well as sharing socio-political themes, require Sampson to alter and push her natural timbre beyond her comfort zone – at time, even, beyond recognition. It’s both exhilarating and disturbing to hear her move out of the sunshine into areas more sinister, scary or strident, as if she’s pointing a torch into the darkest corners of her voice. You get the message that, in singing, it’s also possible to say something.

This ongoing commitment to new writing also features on ‘You Did Not Want For Joy’, Sampson’s 2023 album with lutenist Matthew Wadsworth. Nico Muhly’s beautiful setting of the Hildegard von Bingen text (translated) is the opening, title track of a recital that otherwise revisits material that will be familiar to many. However, repeated listens reveal multiple layers to this brilliant album: it has a unique vibe among similar records I’ve heard, a successful melding of old and new sound. For example, it has a mirror structure that starts and ends with the Hildegard settings, and two versions of ‘I will give my love an apple’ (traditional, and Britten). Including a group of Britten folk song arrangements with Campion, Dowland and Purcell sustains this ancient/modern tension.

Wadsworth’s production makes an extra instrument of the acoustic: there is so much space for the voice and strings to breathe, Wadsworth’s robust playing a perfect partner to Sampson’s honesty and intimacy (try the Purcell settings in particular, or the bravura character-acting in the broadside ballad ‘Packington’s Pound’). At times, I felt like anyone drawn to atmospheric folk acts like Pentangle or Espers would be instantly at home here.

As we career through 2023, it’s worth mentioning some live highlights. During the summer, Sampson joined the Helsinki Baroque Orchestra in a concert-staging of a rare gem, Schumann’s ‘Genoveva’ – a sensitive, steely and ultimately soaring central performance.

She then appeared with soprano colleagues Anna Dennis and Alys Roberts) and players from the Dunedin Consort in ‘Out of her Mouth’, an innovative staging by Mathilde Lopez of three cantatas by Elizabeth Jacquet de la Guerre. In the unusual setting of Village Underground in Shoreditch, the three sopranos each brought a biblical character to life, retelling events from their point of view. Opera as under-the-radar fringe theatre, it had a visceral impact and must have strongly appealed to Sampson’s thirst for the innovative. (You can read my report on ‘Out of her Mouth’ here, and stream it online here – please note tickets to view on demand are available until 24 January, with the playback online until the end of the month.)

Then, in November, Sampson returned to fully-staged opera after some years away to play the role of Créuse in Peter Sellars’s new production of ‘Médée’ at Staatsoper under den Linden, Berlin. It was an evening of electrifying contrasts: Sellars’s bold ultra-modern staging applying an uncompromising vision to the beauty of Charpentier’s score; and – crucial to this version’s power – Magdalena Kožená’s unfettered performance in the title role, grounded by Sampson’s composed dignity as her rival, conveying as much compassion, confusion and anguish with silent gesture and movement as with singing – the still foundation we could hang on to amid the chaos.

So we come full circle, back to the studio, with the release of album #100, ‘but I like to sing…’ Returning to the voice/piano format with Middleton, Sampson has assembled a record that sidesteps a ‘greatest hits’/‘my life in song’ option. Instead, it’s more like ‘a soprano’s self-portrait’: a brand new recital that brings together Sampson’s diverse artistry and interests in a seamless programme. Over time, the recital forms a snapshot of a distinctive musical personality: themes include the sheer love of music (Pritchard, Schubert), humour (Bernstein, Poulenc), passion and sensuality (Paladilhe, Saariaho, Strohl), generosity and collaboration (Middleton’s astonishing piano part in a ‘Nocturne’ by Marx, Jack Liebeck’s guest violin on Strauss’s ‘Morgen’), motherhood (Barber)…

Sampson seizes the opportunity to foreground modern/contemporary female composers. Along with Rita Strohl’s beautiful ‘Bilitis’ settings and Errollyn Wallen’s haunting carol ‘Peace on earth’, the commitment to commissioning new work bring us Deborah Pritchard’s ‘Everyone Sang’, which takes Sampson through both hymnal ecstasy and fragile introspection. There are two songs I feel particularly represent Sampson’s ongoing exploration of her own voice. The Saariaho track, ‘Parfum de l’instant’, has Sampson’s seemingly-impossible epic high-notes barely constrain the emotional tumult of Middleton’s piano.

However, she flies completely solo on one of my favourite songs on the whole album, Cheryl Frances-Hoad’s ‘Something More than Mortal’, for unaccompanied voice. The song sets text from Ada Lovelace’s letters to Charles Babbage. As such, when Lovelace describes the power of her imagination, the vocal line stretches out towards the infinite possibilities; then, when she gets to work, the syllables become rapid-fire, tripping, refreshing and re-booting, evoking a ‘machine-code’ chatter. It’s instantly intriguing (is the ending as ambiguous as it seems?), the dexterity of the performance utterly riveting.

I would have loved to write about all of these releases at even greater length, but time and circumstance overtook me. So, I decided to make amends with this appreciation in early to mid December. But – plot twist – I would not have dared script this particular ending. As 2023 drew to a close, Sampson was awarded an OBE. Thrilled and delighted by this news. What year could be more appropriate for her to receive this recognition?

AA

The featured photograph for this post is by Marco Borggreve.

Here is a playlist drawn from the 2023 releases discussed below. Please note that I’ve used Spotify purely for convenience here. If you want to pay for your music, hear it in high quality and enjoy the song texts, sleeve notes and so on, we recommend Presto Music. You can buy actual CDs, downloads or subscribe to their excellent streaming service.

Discover more from ARTMUSELONDON

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One Comment Add yours