This collection of more than 50 portraits painted by Francis Bacon is certainly intense – although perhaps not for the reasons one might have expected.

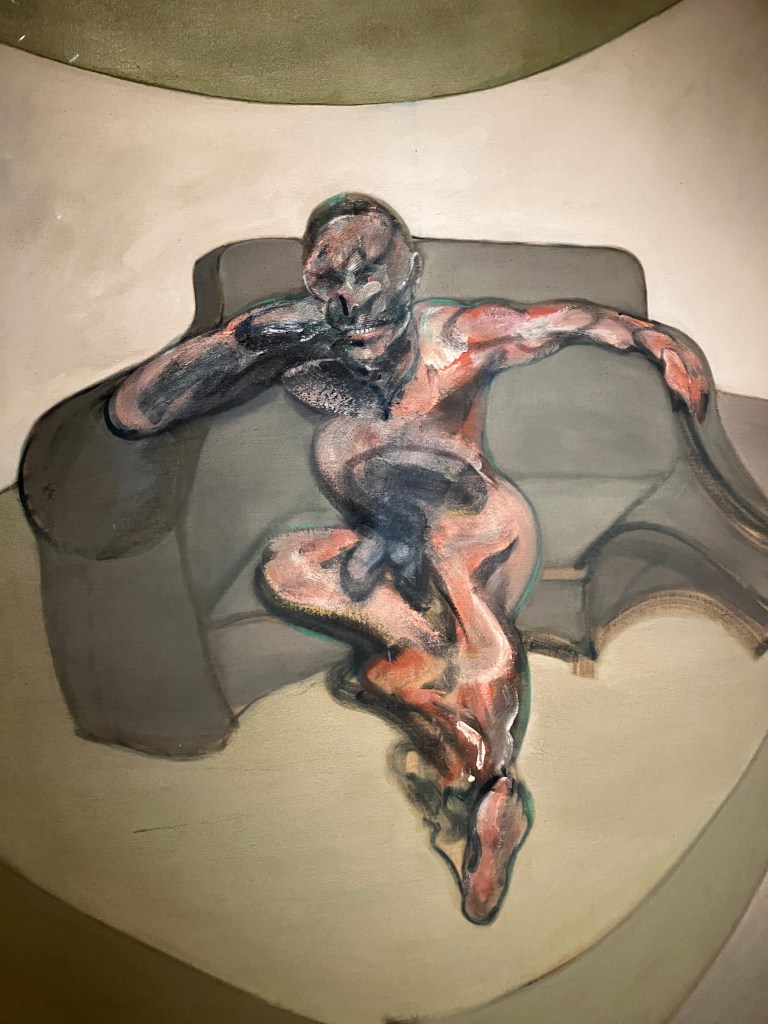

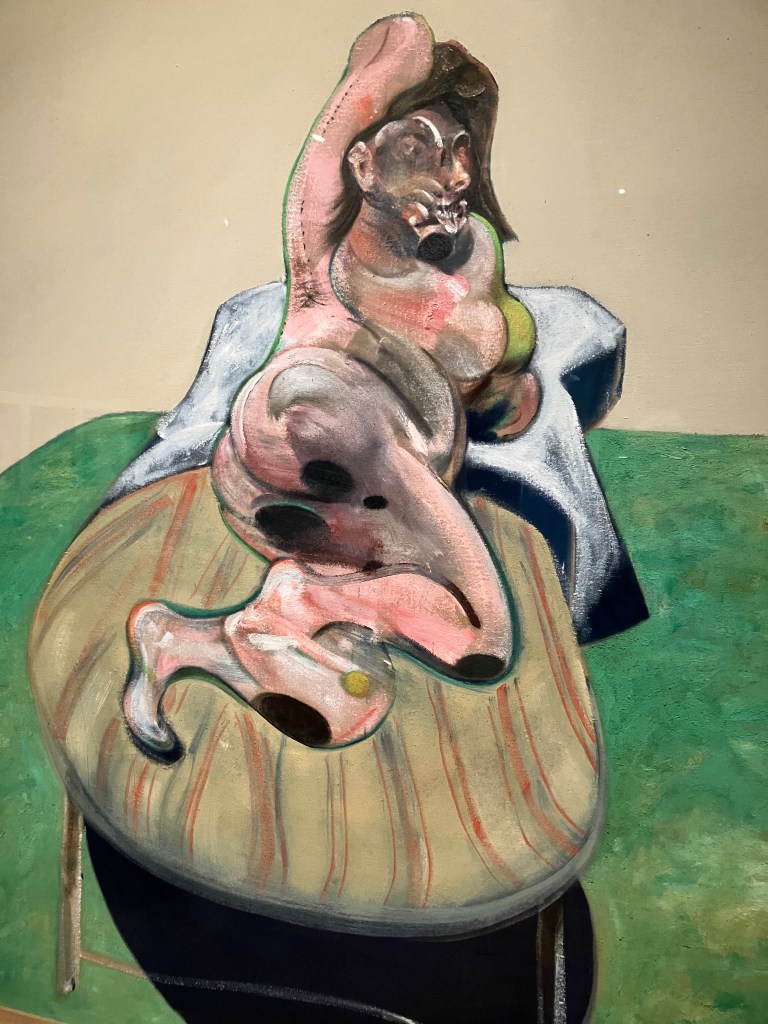

Some of Bacon’s most famous and celebrated canvases show extremes of violence and distortion: the full-on body horror of the early figures at the crucifixion, or the melting abyss of a screaming pope. When displayed as stand-alone exhibits alongside other artists, the effect is even more arresting, a visual roar from some non-parallel universe.

So I was curious – and possibly a little apprehensive – about seeing Bacon’s work across an entire exhibition. However, thanks to the choice of works and the deft hang, the experience is engaging and compelling. Instead of a single canvas providing an exclamation mark, a shriek into a show’s silence, the cumulative power of the paintings builds into a narrative. Ultimately, the exhibition succeeds in assembling a portrait of Bacon himself, reflected through his subjects.

There are a number of ways the visitor can assemble the jigsaw. Ironically, I felt like I found the ‘missing piece’, the picture that unlocked the whole show for me, before I’d really begun putting the rest of the puzzle together. After fracturing a bone in his face, Bacon went on to produce a self-portrait with a swirl of black paint obscuring his eye and cheek.

While Bacon was clearly not an artist who strove for ‘accuracy’ in the realist sense, this is like a kind of hyper-realism, to record how the injury felt, what it meant – what it actually looked like was of least importance.

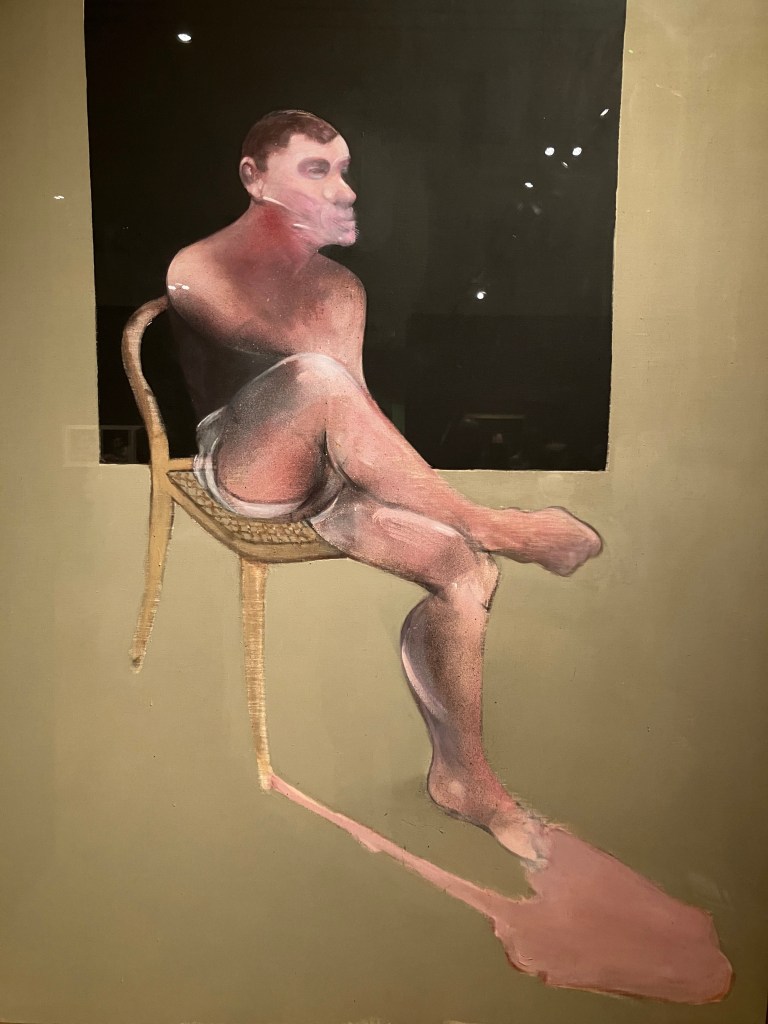

If the aim or mark of a good portrait is to convey a key element of the subject’s character alongside their appearance, Bacon seems to want to bypass ‘appearance’ altogether and put everything else he perceives about the individual on the canvas.

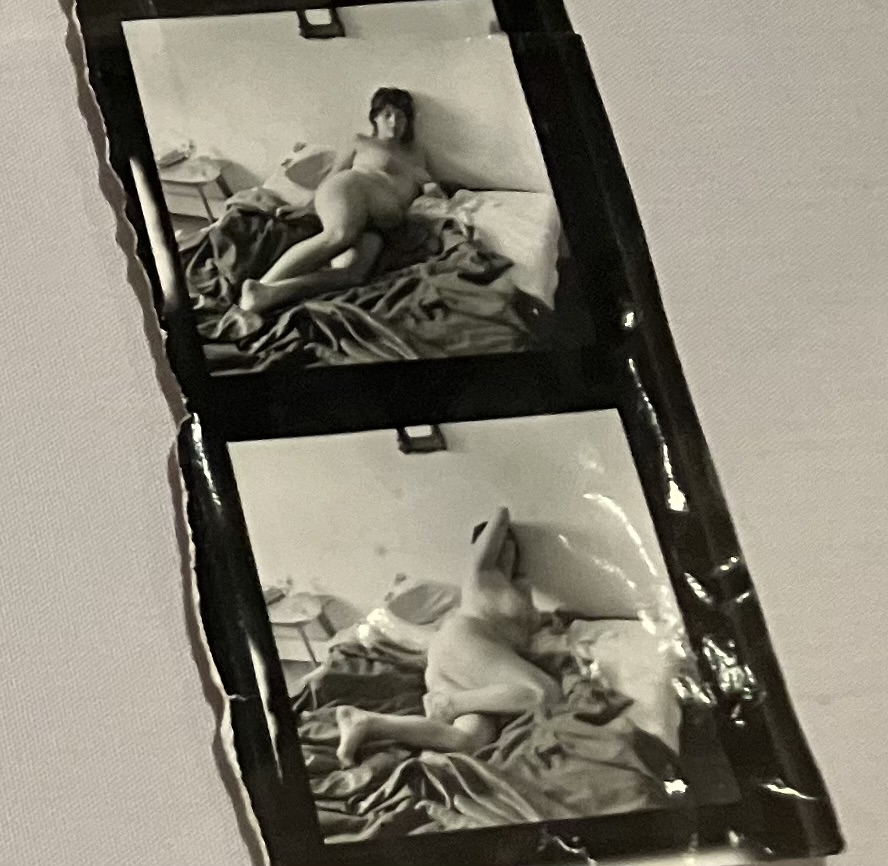

Perhaps his self-awareness, his acknowledgement of the intrusive aspects of his process, is one of the reasons he preferred to work from photographs of his sitters, shrinking from the claustrophobic intimacy of painting from life.

I wonder if this ‘at-one-remove’ technique also fed into the ongoing lines and boxes motifs in his work, with Bacon positioning himself, as well as us, in scientific observer mode, trapping his models in glass cases and reflecting shards of light.

There is a fascinating excerpt from a television interview Bacon gave to David Sylvester (a supportive arts journalist). It’s a brilliant period snapshot in itself – the two men are in earnest conversation, cigarette smoke curling upwards from their hands – as Bacon describes the ‘injury’ he unwittingly causes his sitters. As the exhibition notes tell us, John Deakin – who took many of the photographs Bacon used – referred to the artists’ subjects as “victims”.

But instead of creating something almost unbearable, bringing these paintings together in fact provides an opportunity to place the more shocking images in context and see the work as an ongoing chronicle or project. What intricacies we may know or not know about the volatility and (self-)destructive nature of Bacon’s life, lovers and relationships seems represented, clearly, for us to infer. However, we also see where there is tenderness and sympathy, and gain an insight into how Bacon might have handled (or otherwise) those emotions.

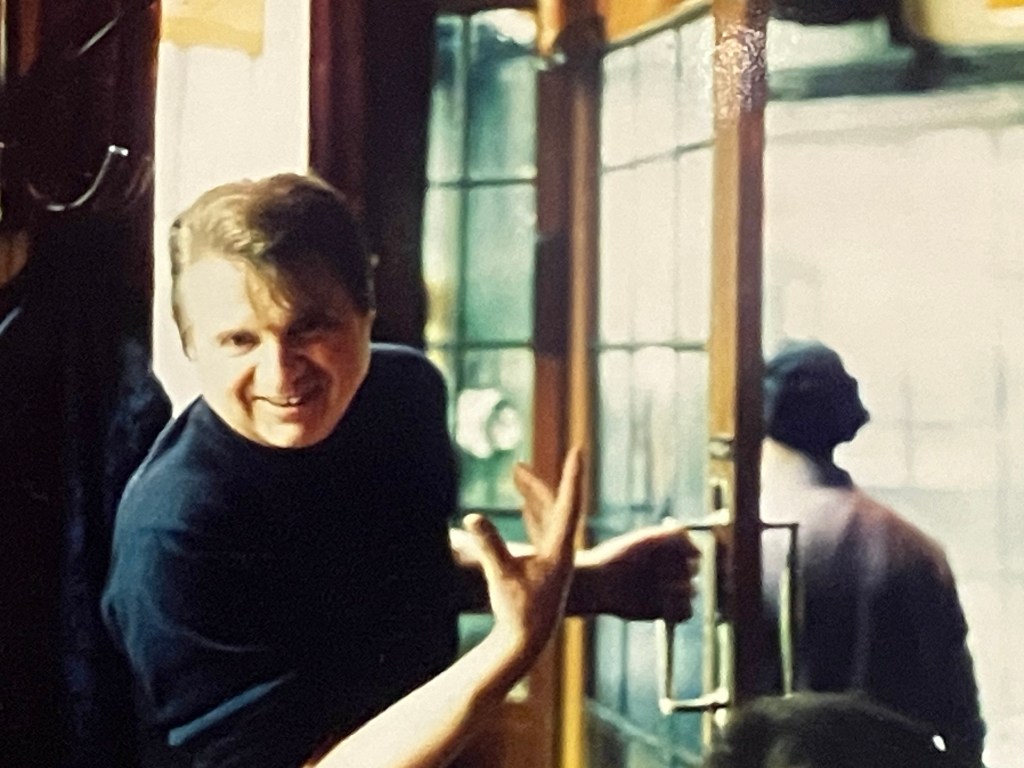

The documentary photography that features throughout the exhibition is especially important in this respect. Most of the iconic shots of Bacon that I was already familiar with are present and correct. Arnold Newman’s portrait of Bacon beneath the lightbulb, spontaneously framing him in an echo of his own boxes, is a wonder. However, I think it is important that we also see Bacon laughing, socialising, at ease, and keen to interact with other upcoming artists who showed an interest in him.

In 1969, Bacon took part in ‘Heads’, a project by Peter Gidal (a film artist who was still a student at the time). Gidal films a static Bacon in extreme close-up, again trapping him in box. There’s no scream, just Bacon’s haunted, almost blank expression. One wonders what imaginary version of Gidal might have been forming in his head as he looked into the lens.

AA

The exhibition runs at the National Portrait Gallery until 19 January 2025.

The main image for this post is ‘Study of the Human Head’, 1953.

Photos from the exhibition visit by AA.

Discover more from ARTMUSELONDON

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great review, thanks. Well chosen images

LikeLike