Our recent Swiss holiday closed with a lightning visit to Opernhaus Zürich, to catch two performances in one day: a matinée of Monteverdi’s ‘L’Orfeo’, followed by a staged version of Mendelssohn’s ‘Elias’ (or ‘Elijah’).

Both were rewarding experiences. I had never seen a production of ‘L’Orfeo’ before (a rather important omission, now happily rectified) and I was unfamiliar with the cast – so the effect was of one delightful discovery after another. The score was beautifully played by Orchestra La Scintilla under Octavia Dantone, clear and expansive in the house acoustic, and with what felt to me like a real sensitivity and delicacy, even in the more dramatic and propulsive moments. The music felt for the characters as it helped create them.

On its appearance in 1607, ‘L’Orfeo’ was a creative milestone, the earliest ‘opera-as-we-know-it’ in the repertoire. Evgeny Titov’s production honours this innovation with a bold, stylised staging, some intriguing narrative devices and a couple of genuine ‘did I just see that?’ coups de théâtre. He throws some startling ideas at the piece, as if insisting this masterpiece can take it – and it works.

One especially moving element is the suggestion that Euridice is eternally absent, her fate foreshadowed from the opera’s opening seconds (where we first see her motionless in her coffin) – her earthly life as transient and elusive as her temporary near-return from Hades. This gives the action a circularity, until this too is disrupted by a telegraphed, but still thrilling, final twist.

The singers all made their marks. First among equals: as the doomed couple, Kristian Adam brought you to the point of conviction that Orfeo’s music could bring anyone, human or god, under its spell, while Miriam Kutrowatz portrayed a still-loving, but slightly reserved Euridice, never quite within Orfeo’s reach. The chorus (the excellent Zürcher Sing-Akademie) in their ghostly white make-up, a part-corpse, part-clown Carnival-of-Souls cabaret, were perfectly suited to the ne(i)therworld of Titov’s imagination.

Mirco Palazzi was an absolute stand-out in the roles of Caronte (Charon, ferryman to the dead) and Plutone. Offstage, he plays a crucial part in one of the key staging effects I mentioned earlier, his resonant bass amping up (or amped up, perhaps – beware, purists!) the power, even terror, of the moment.

As you can tell, I’m avoiding spoilers here: it seems the right thing to do, as this is a revival of a production that premiered only a season ago. It will surely be back again.

Andreas Homoki steps down as Opernhaus Zürich’s Artistic Director this season, making ‘Elias’ his final production for the company while still in the role. I was lucky enough to see Homoki’s compelling ‘Ring’ Cycle at Zurich in 2024 – so I was intrigued by his choosing ‘Elias’ for a swansong: after perhaps the ultimate operatic endeavour, he was drawn to the other extreme, a ‘non-opera’ of sorts, a blank canvas.

Dramatisations of oratorios are not exactly uncommon, but it’s interesting to ask: why? In theory, they shouldn’t need it: nothing ‘extra’ to distract from the sacred subject matter. The narrative drive and vivid characterisation in ‘Elijah’ are certainly enough in themselves to create and sustain a riveting story. However, these must be the exact qualities that would make it such rich material for a director.

In particular, the roles are so complex and affectingly drawn that they especially reward – demand, even – fine actor-singers. (A recent ‘Elijah’ I saw in Cambridge, UK, that featured Simon Keenlyside and Carolyn Sampson, was a shining example of this, their naturalistic acting skills creating a transformative realism within the conventional oratorio setting.)

Christian Gerhaher was extraordinary in the title role. I fully expected the haunted quality he gave the prophet, an almost-reluctant kindness, physically shouldering the burden of knowledge, dread and guilt. But the commanding aggression, when required, was there too, the voice losing none of its dark beauty even with the volume dialled up.

He was matched by Julia Kleiter as the Widow, both free and able to bring vivid gesture and movement to the resurrection scene, the grief almost palpable. This is vital because, in Homoki’s version, the outcome of this miracle causes ripples throughout the action (again – I’m wary of spoilers!) – a recurring character takes on a motif-like function, drawing us deeper into Elias’s psychology. I was reminded – a tangent, I know – of a famous scene from ‘The Last Temptation of Christ’: return from oblivion unchanged is impossible.

It was fascinating to see directorial touches that gave me ‘Homoki Ring echoes’ and felt part of a consistent vision. Semi-abstract, multi-purpose set fixtures to suggest various locations; revolving stage and concealing partitions to energise and animate the action without relying on constant movement from the performers; unfussy symbolism (here, cascading paper planes – simultaneously evoking doves of peace and the spreading of the Word – conjured an austerely beautiful image); effective, economic costumes.

The outfits were in fact crucial to what I think was one of Homoki’s most impressive achievements with this interpretation: his success in making the chorus a fully-realised hive-mind character. There were a handful of different clothing styles spread across all the singers – with the effect of dividing them into sections, almost teams. At times, they would ‘socialise’ together or at others, intermingle. In this way, they morphed from voices representing the ‘masses’ into a crowd of real people, the various uniforms signifying a mix of race, creed or class, their changes of allegiance magnified and satirised.

A coincidence, no doubt, but ‘L’Orfeo’ and ‘Elias’ made an effective, if accidental, double bill – both offering thought-provoking angles on loss, grief and the internal, eternal struggle between doubt and belief. Elijah’s ascent to heaven is ambiguously and modestly handled – his achievements accomplished: rather than climb the obvious stage set, he moves behind it, a split-second blaze of flame signalling his disappearance, unseen. One wonders if this had an ironic appeal for the also-departing Homoki.

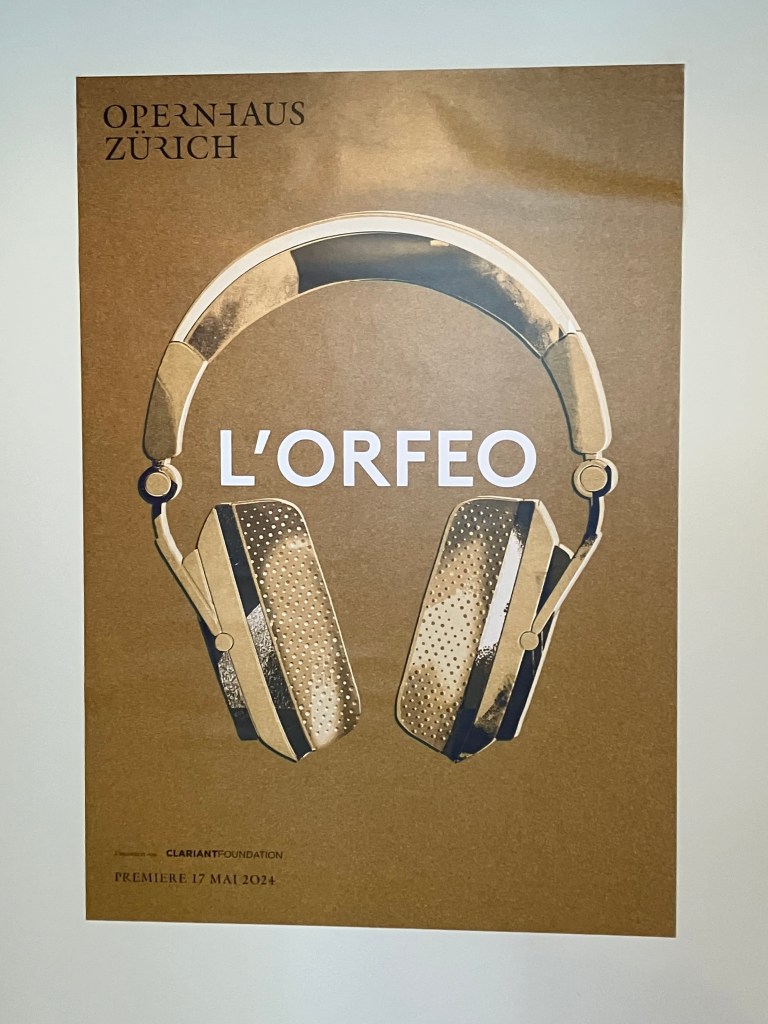

During Homoki’s tenure, illustrator François Berthoud has designed the distinctive posters for all of Opernhaus Zürich’s productions, a collaboration lasting 13 years. We were fortunate to catch the temporary exhibition displaying these posters throughout the venue – take a look at the ‘companion’ post to this one here.

AA

Opernhaus and curtain call photos by AA. Production gallery photos by Monika Rittershaus.

Discover more from ARTMUSELONDON

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One Comment Add yours