The latest in the Royal Opera’s Janáček cycle, this is their first production of ‘The Makropulos Case’ – and mine, too. I was excited to be seeing at last this piece that I’d read about but, appropriately enough, had difficulty imagining as a real experience.

Please note that this write-up includes ‘spoilers’ to a certain extent, so I can freely discuss key aspects of the production. On the date I upload this piece, there are still two performances left, with discount tickets available (details below). If you’re interested in going, stop reading now, with my blessing – as long as you come back afterwards.

From those of his operas I’d seen (and loved), this composer seemed both eccentric and uncompromising, a chaser of extremes – whether the brutal realism of ‘Jenůfa’ or the full-bodied fantasia of ‘The Cunning Little Vixen’. This story, however, of an ‘immortal’ woman finally facing death due to legal wrangles blocking her access to the elixir’s formula – part haunted house, part Bleak House – threatened to smash the paranormal into the prosaic. I took my seat with no idea what to expect.

Except… that isn’t entirely true. Because this was also the latest production for the RBO by director Katie Mitchell (and, I understand, the last, as she has decided not to continue working in opera). Mitchell’s long and prolific career across both theatre and opera runs into a hundred or more productions, so I am assuming that she is the only person who has seen them all. However, from that vast body of work, critics and audiences have broadly identified a signature ‘Mitchell’ style, with key features and themes recurring throughout her interpretations.

I’ve witnessed this over what I believe is a useful representative sample – that is, her major productions for the Royal Opera: ‘Written on Skin’, ‘Lucia di Lammermoor’, ‘Lessons in Love and Violence’, ‘Theodora’ and now ‘The Makropulos Case’. Full disclosure: I liked them all, and this latest venture, in particular, prompted me to think about why.

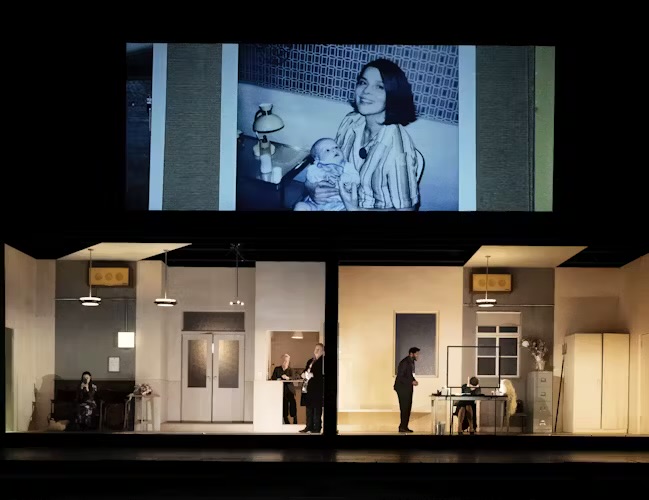

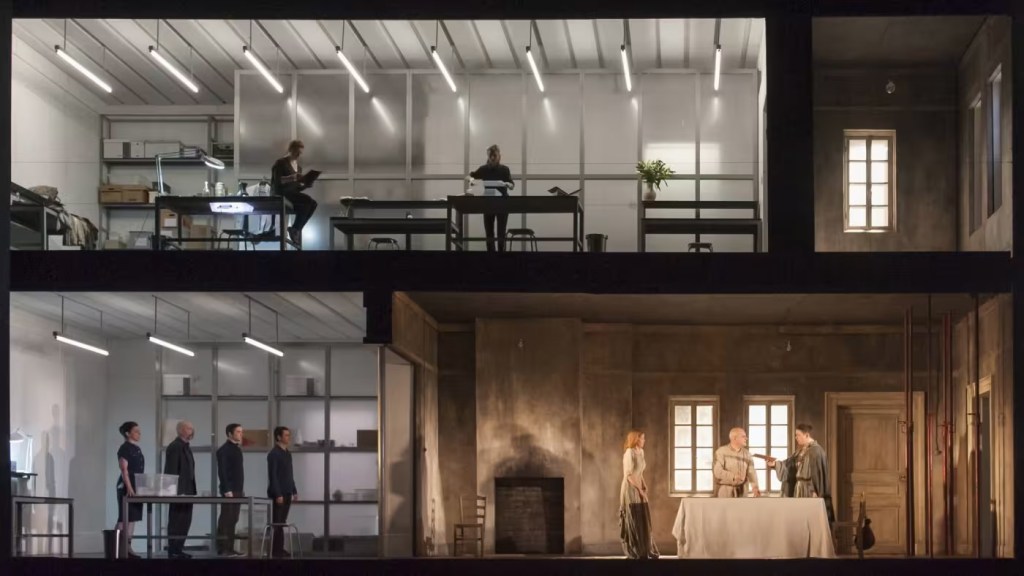

When recalling the impact of ‘Written on Skin’, it’s probably helpful to consider some of Mitchell’s motifs ‘out loud’. Dividing up the stage into sections or boxes – sometimes to control precisely where we need to look, or at others to present multiple strands of action simultaneously. Playing with time, moving the onstage performers in slow-motion to emphasis key stage business. Disrupting any notion of onstage reserve, leaning into the uncomfortable, the unsavoury. Making us confront violence head-on.

‘Written on Skin’, then a new opera, demanded our belief in a timeless, supernatural admin team of angels interacting with a firmly-rooted, fixed-in-time medieval domestic tragedy. It could not have asked for a better fit than Mitchell’s compartmentalised, near-SF presentation and visceral direction – and unfettered response – of leads Barbara Hannigan and Christopher Purves.

It’s tempting to view Mitchell’s Royal Opera work as an unofficial sequence in itself, as the level of reinterpretation builds and builds. In the now famous/notorious staging of ‘Lucia’, Mitchell reacted against the heroine’s offstage demise by showing her suicide alongside the actual action of the opera.

Back to a new Benjamin opera for ‘Lessons’, the ‘Palace’ of the text arrived in the modern-day with multiple PoV ‘shots’ on the same space. And, while adding staging or visual narratives to oratorios is hardly a practice exclusive to Mitchell, few who saw her production of ‘Theodora’ will forget its 18-certificate taboo-busting, table-turning terrorist treatment.

I sat stunned as the curtain fell on ‘The Makropulos Case’, trying to process everything the previous 100 minutes or so had thrown at me. Thinking through it all afterwards, I feel that it contains all the elements I mention above, and ramps them up even further.

The simultaneous multiple viewpoints are used to scintillating effect, especially in the opening hotel sequence which dares to flirt with bedroom-farce timing despite the gravity of the situation. Working again in a modern setting, Mitchell overlays the original story with an entirely new parallel romance plot – what goes unsaid in the libretto plays out not just physically on stage but through a dizzyingly swift series of text message chats projected above the action. The precision timing with which these often explicit exchanges interact with and illuminate the drama is a bravura piece of stagecraft. The exhilarating speed of it all meant that when the sparingly-used slow motion snapshots did arrive, they landed with maximum impact. This manipulation of time felt especially pertinent to an opera whose central character is trying to do the same thing, freezing moments of excitement to punctuate the ennui of immortality.

Mitchell’s approach has been described as ‘cinematic’, and as a film enthusiast, I suspect this is the main reason I’m so drawn to it. When I think of other opera directors noted for their own ‘signatures’ – say, Peter Sellars, RIchard Jones or Barrie Kosky – I don’t see much common ground. But noting a few reference points from the movie world… There’s a rich vein of horror in particular running through the violent visual motifs, and ‘letterbox’ or ‘split screen’ vision control (Carpenter or De Palma, say). There’s the obsessive balance / doubling and detached observation of Kubrick – and, certainly in the case of ‘The Shining’, the willing departure from the original creator’s vision in favour of his own. There’s the time-bending, space-shifting storytelling of Nolan, his expectation that audiences will keep up, and absorb parts of the information overload subconsiously.

I’m aware that I’m mentioning some ‘big hitters’, ‘alpha male’ directors – but that seems to me partly the point, as Mitchell is absolutely A-list, mainstream in her field. Might she polarise opinion for sharing characteristics male auteurs are lionised for? That said, it would be wrong to overlook the challenging focus on body (bodily function?) horror from women directors in recent years – Glass’s ‘Saint Maud’, Fennel’s ‘Saltburn’ and, of course, Fargeat’s ‘The Substance’. Or the non-linear timeframes of Gerwig’s ‘Little Women’ or Bigelow’s ‘A House of Dynamite’.

I think these are commonalities rather than direct, actual influences. (And any given artist will have a thousand direct, actual influences the rest of us can never know.) However, I also believe that the ‘Mitchell operatic universe’ brings genuine brio and originality to the form. ‘The Makropulos Case’ in particular leans into multiple-channel, short-attention-span mental gymnastics and arguably presents an idea for one way the nebulous younger audiences sought so ardently by the arts scene might connect with opera. You don’t dumb it down; you change it up.

I don’t believe her work is beyond criticism, certainly of the practical kind. Should you create stagings where some of the audience can’t see everything? Should you make massive changes to the plot, if it means people might not understand what’s happening? I don’t see these as ‘yes or no’ questions, as it will always depend on a number of moving parts: the power of the idea, the context for the production, the interpretation of the performers. Crucially, though, I don’t think these are considerations only for Mitchell.

While you might expect Mitchell’s vision to dominate, there are many other reasons to see ‘The Makropulos Case’ if you can. The lush, dynamic soundtrack of a score fills your senses as much as the visuals, thanks to an orchestra on fire, in the hands of new RBO music director Jakub Hrůša (who, understandably, utterly inhabits Janáček alongside other Czech repertoire).

Amid an outstanding cast, in the lead role Ausrine Stundyte manages to maintain Emilia Marty’s ambiguity, walking the fine line between heartfelt, passionate interactions with her would-be lovers, while remaining elusive, somehow outside it all: commanding and charismatic. In all that’s going on, you will be unlikely to take your eyes off her.

AA

There are two remaining performances of ‘The Makropulos Case’, on 19 and 21 November. While the current offer lasts, you can book tickets at a 20% discount by entering the code EXCLUSIVE20 when you reach the ‘How would you like to find your seats?’ page.

Discover more from ARTMUSELONDON

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.